When The

Crowds Have Gone

Why are mental health issues

so common in retired athletes?

There’s something uniquely joyous about Sports Personality of the Year. The shortlist for the annual BBC award will be announced in the next few days before a star-studded ceremony in Salford on 19 December, at which millions of us will reflect on a remarkable year for British sport: a young woman from Bromley producing a tennis fairytale in New York; a diverse young England squad carrying the nation to its first men’s football final since Bobby Moore led the team in 1966; Team GB bringing 65 Olympic and 125 Paralympic medals home from Tokyo.

Behind every public triumph is a private story of hard work, resilience and sacrifice which leads our finest athletes to be put on a pedestal as role models, even national heroes. But here’s the part we don’t really talk about: that glory is fleeting, the spotlight soon moves elsewhere, and the darkness that remains can be terrifying. The result is a hidden epidemic that has affected retiring sportspeople at all levels, including several past recipients of that prestigious BBC trophy.

Andy Murray is one such example. After becoming the only three-time Sports Personality of the Year, including both of the years when he won Wimbledon, he suffered a career-threatening hip injury that left him with chronic pain and the prospect of being forced to quit the sport that had consumed his life. “I’ve spoken to sports psychologists and stuff,” he told The Telegraph in 2019. “I don’t know exactly what depression feels like, but I was definitely very low, and at different stages feeling quite lost.”

Murray’s case is far from unique. Recent studies by organisations including the International Olympic Committee, the BBC and the Professional Players’ Federation have all found that an alarmingly high proportion of sportspeople struggle after retiring.

When Sport Is Who You Are

Part of the issue seems to be that success in sport often entails an all-consuming dedication from an early age, meaning that by the time young athletes become adults they may not have developed friendships, hobbies or other interests in a way that most people their age do. “The sport becomes who they are,” said Gary Bloom, a sports psychotherapist and broadcaster. “They entwine their personality, their psychological landscape, just about everything about them gets wound up in their sport.”

The problem is that all sporting careers must one day end, at which point the person left behind can feel as though their entire life’s purpose has been snatched away. In some cases, especially when a career was ended prematurely by injury, the athlete might have to come to terms with regrets that some of the goals on which their entire existence had been focused will now never be reached. For others, the problem might be the opposite: having reached the pinnacle of their profession they worry that nothing else in their life will ever feel as good in comparison. “I've come across athletes and coaches who are the most depressed they've ever been after success,” Bloom added. “All of a sudden their ‘why’ is gone.”

One thing that isn’t gone after retirement for most athletes is the need to continue working: despite perceptions that all professional athletes live a lifestyle akin to a top Premier League footballer, the economic reality for most is not dissimilar to the rest of the population. The median salary in football’s Women’s Super League was still under £27,000 as recently as 2018, while men playing at the elite levels of rugby league and rugby union earned £40,000 and £70,000 respectively - decent money perhaps, but not enough to permanently stop earning in their mid-thirties. The vast majority will need to find new streams of income in the next chapter of their lives.

Of course, in addition to those who struggle there are also plenty of sportspeople who manage to find that second career without significant financial or psychological difficulty. Kathy Begley is a great example, having made the jump from horse racing to studying veterinary medicine at one of the world’s top universities.

Congratulations @KF_Begley winner of @IJF_official Progress Award who used JETS to help her complete a fast track self study A level whilst working, passing with the A* grade she needed to get a place at @StEdmundsCam Cambridge University to study Veterinary Medicine pic.twitter.com/St30cMSjw5

— JETS (@JETS4Jockeys) November 11, 2021

So why is it that some flourish at that moment of change while others flounder? According to Simon Taylor, chief executive of the Professional Players’ Federation (PPF), the more seamless transitions are often enjoyed by those who have laid the groundwork well before their playing days are over: the ones who have made the most of their contacts while they enjoy celebrity status, have mingled in the corporate boxes of their stadiums, and have used their downtime to plan for what’s next. “It’s an old cliche that failing to prepare is preparing to fail,” he says. “I think almost all sportspeople would know about that on a sports pitch, but it's even truer about your life after sports.”

Fortunately it seems that over the past 20 years a lot of clubs and player associations have developed services to help aid the transition. Rugby and cricket may be among the best-equipped: both have dedicated Player Development Managers (PDMs) who will work with players regularly on their long-term plans from the early stages of their careers, and who can point them confidentially towards mental health assistance where necessary.

In 2017 an independent report by Baroness Tanni Grey-Thompson, commissioned by the UK government, made recommendations about further steps that clubs could take. These included a requirement that retiring athletes be provided with information about support and opportunities to retain contact with the sport after they leave - something that many clubs have taken steps to address, , although the available resources differ significantly by sport.

SUPPORT IN FOOTBALL

- The Professional Footballers' Association (PFA) provides a 24/7 counselling telephone helpline for current and former footballers.

- Any current or former player who is experiencing severe financial difficulty can apply for support from the PFA Benevolent Fund.

- Current and former players are eligible to apply for funding towards courses that lead to nationally recognised qualifications.

- Grants are available for retired footballers who may need medical support for injuries suffered in the course of their football career.

SUPPORT IN RUGBY UNION

- A team of Player Development Managers (PDMs) provides support, with some PDMs assigned specifically to players who are retired.

- Restart, the charity arm of the Rugby Players' Association (RPA) , provides grants for current and former players suffering from emotional, financial or medical difficulties.

- 24/7 counselling available to RPA members, as part of its "Lift The Weight" mental health campaign.

SUPPORT IN RUGBY LEAGUE

- Rugby League Cares, the sport's official charity, provides a full-time Player Welfare Manager at each club in the Super League.

- The Rugby League Benevolent Fund provides financial support for retired athletes who suffered serious injury through playing the sport.

- Funding is available to former players for training, education and to help with periods of financial hardship.

SUPPORT IN CRICKET

- The Professional Cricketers' Association (PCA) provides regional Personal Development Managers who help every registered player to make a written plan for their personal development.

- The PCA Futures Conference every November helps current players to prepare for a career after cricket .

- The Professional Cricketers' Trust provides financial support, educational programmes and a 24/7 counselling service.

Photo: Mattythewhite, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Mattythewhite, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Switching The Play

Help is also available from several not-for-profit organisations that exist within particular sports to help athletes with their mental health. The Switch The Play Foundation is the UK’s only charity that helps athletes across all sports to enjoy a successful transition to life outside the bubble of elite competition. It runs Switched On, a free membership service that provides support and guidance on topics including financial well-being, change management and career opportunities. It also runs intensive six-week intensive boot camps for those who are either preparing to retire or have recently done so, and works with clubs and other organisations to help them provide better services. Numerous fundraising events support its work, and in the first week of December it is taking part in The Big Give’s Christmas Challenge, through which any donations made will be doubled by another donor.

Piero Mingoia, 30, is among those who has benefited from the support provided by Switch The Play. Having been spotted by Watford Football Club at the age of 13, he came up through their youth system and eventually played for them in the Championship, just one step below the Premier League. He then moved down two divisions to Accrington Stanley and later Cambridge United, by which time he was actively thinking about what he might do when he hung up his boots. “I started to see the bigger picture for myself and I started exploring other areas outside of playing,” he said. “Deep down I knew the things I would do outside of football would be things I could do for a lot longer.”

Mingoia discovered Switch The Play through an ex-teammate who now works with them, and signed up for one of their boot camps, which took place over Zoom this summer. Every week his group had talks from different guest speakers on subjects like self-awareness and communication, as well as networking sessions with useful contacts from other industries. The camp confirmed to him that he was doing the right thing in starting to explore his next steps and, although he still does not describe himself as having retired from playing, he is not signed to a club this season. Instead he divides his time between coaching football and a new performance coaching business, aimed both at clients from inside and outside of football.

Unfortunately not everyone is as forward-thinking as Mingoia, and part of the reason that incidences of mental illness among retiring athletes remains so stubbornly high is that a lot of people in his position simply do not access the help that’s available while their careers are still active. In some cases this can partly be explained by hubris: elite athletes tend to be very self-confident by nature, and this can mean that even if they hear horror stories about other people’s transitions to retirement they might complacently assume that they won’t fall victim to the same thing. They also might overestimate the ease with which they will learn a new way to make a living.

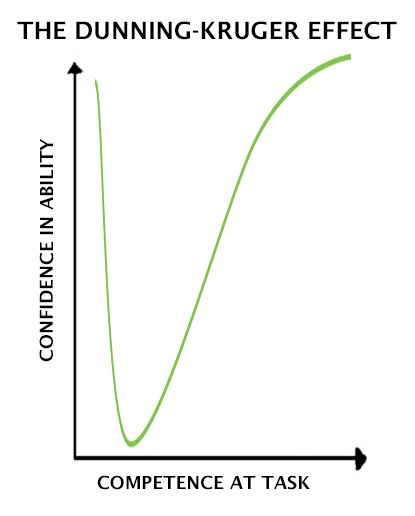

Richard Thorpe, a performance coach and Director of Rugby at Chinnor RFC in Oxfordshire, describes this in terms of a psychological concept called the Dunning-Kruger effect: humans naturally have low competence in skills they haven’t learned yet, but tend to have high confidence in their ability until they start. “Over time [that confidence] dwindles,” he said. “If we carry on our competence increases and our confidence increases again, so if you draw it on a graph it’s a U-bend.” The problem with retired athletes trying to learn a new skill is that they hit the bottom of the bend while also trying to deal with an identity crisis, and can therefore get stuck down there for a number of years, developing anxiety or depression in the meantime.

Changing Attitudes

Another obstacle to athletes coming forward to access support for their transition can be attitudes within the bubble of their sport. Mingoia admits that if he had brought up the idea of making post-career plans with his teammates while still playing football full-time he believes their response would have been dismissive, and that coaches may even have frowned upon such behaviour in case it served as a distraction. “I get why it’s like that,” he said. “You're in the game to get results, so they want your full concentration on playing and doing well for the team.”

Dr Alan Currie, a psychiatrist who sits on the mental health panel at the English Institute of Sport (EIS), agrees that there is a risk of distracting an athlete if the timing of these conversations is mishandled. “As soon as you say to an athlete, ‘there's more important things in life and you have to start developing a wider range of things’, there's a risk that you detract a little bit from the hunger of performance,” he said. “You really don’t want to be going to your last Olympics thinking that it’s not that important and it doesn't really matter. So it is a bit of a delicate balance.”

Still, if that balance is struck then there is evidence that transition planning can actually be a help rather than a hindrance to on-field performance: a 2019 study of rugby league players in Australia found that athletes who plan their retirement ahead of time may actually perform better on the field as a result, and these findings are supported by mounting anecdotal evidence.

That shift in mindset seems to be underway within professional sports when it comes to mental health: when world-famous competitors like tennis player Naomi Osaka and gymnast Simone Biles have pulled out of major competitions this year to prioritise their well-being, the response was largely (although not universally) supportive. According to Simon Taylor, some of the newer coaches in elite level sport also seem to be open to a more holistic approach to the athletes in their care, including the current England men’s football manager. “Gareth Southgate completely gets that the people he works with are more than just footballers and almost encourages them to take a wider social responsibility,” he said. “Thankfully, [the attitude] is long gone that if you’re preparing for life after sport then you’re preparing to fail as a sportsman.”

Ultimately, of course, the numbers don’t lie and at the moment it remains true that mental health concerns in retired sportspeople are far more common than those working in the sector would like. It is only if those statistics have improved in five or ten years from now that the industry can claim real progress, but it seems that there are reasons to be genuinely optimistic. Piero Mingoia certainly has no regrets that he accepted the help that was available to him, and having already made it in one notoriously difficult industry he seems to be in no doubt that he’s going to be fine in another. “For 10 years I was a professional footballer,” he said. “If I adopt the right attitude and the right mindset again, it's only a matter of time before I get to where I want to be.”

If you have been affected by any of the issues raised in this article, there are details of organisations that offer advice and support around mental health on the BBC website.

All photos in this article are by the author unless otherwise stated.