The benefits of boxing - the people who have punched their way to change

Tyson Fury isn't the only one who has transformed his life using boxing.

Growing up with abuse, boxing coach Andy Whitehall’s youth was characterised by unrest. Like many who suffer trauma, Whitehall was “in fight or flight all the time”.

“Those were my two options and I was never much of a runner, so I would always react to a threat... I would react with aggression,” said Whitehall.

At school in West Ham where he grew up, he would lash out at small things like someone looking at his girlfriend or pushing into the dinner queue.

But Whitehall gradually became poised — a change he attributes, perhaps ironically, to the violent sport of boxing.

Today, the 52 year-old has a wholesome life. He’s a former police officer turned school teacher, and owns a boxing gym called The Right Stuff in Staffordshire. Since officially opening in 2009, it has helped hundreds of children improve their mental health and transform their lives in many other ways.

Andy Whitehall (left) and boxer Amy Nolan (right) who he coaches boxing. Credit: Right Stuff Boxing

Andy Whitehall (left) and boxer Amy Nolan (right) who he coaches boxing. Credit: Right Stuff Boxing

But Whitehall and his students are not the only ones who have transformed their lives through boxing.

Tyson Fury, who went from the brink of suicide to world champion for the second time, has been vocal about how boxing, coupled with family support, pushed him through his darkest moments and continues to help his mental health.

Moreover, Whitehall's gym is just one of many grass-root boxing clubs changing the lives of young people.

So, what is it about boxing that makes it such an effective tool for changing lives?

The paradox of violence

For some people it might be hard to imagine that boxing has any profound benefits for society. There’s a history of fighters going in and out of jail to fuel this doubt.

Mike Tyson, perhaps the most famous name in the sport’s history, served six years in prison for rape.

Moreover, when Tyson was 15, his boxing coach Teddy Atlas pointed a gun at his head after he was caught harassing Teddy's niece.

In 2019, researchers at Manchester Metropolitan University suggested that many boxing gyms are a hub of ‘hyper-masculine’ talk; a place where homophobic slurs are commonplace, women are excluded, and violence is perceived to be a solution for problems.

But this is only part of the story. Boxing in many cases seems to promote virtue rather than vice.

Fighting antisocial behaviour with boxing

Every year, local authorities invest millions of pounds into community boxing gyms because they understand the value of boxing in terms of helping people's mental health and tackling antisocial behaviour.

Whitehall’s Right Stuff Boxing, for example, is funded entirely by Staffordshire Council and Police.

And in June 2021, London’s City Hall invested into grassroot boxing gyms, such as Dwaynamics, as part of a £10million programme of intensive early intervention for children aged 10-16.

The researchers at Manchester even concluded that boxing can be a “great hook for change” as boxing clubs offer a space for self-development, inside and away from crime and county lines violence.

‘Less time on the streets’

Denzel Greaves from Northolt, London was 14 when he started boxing. At the time he was teetering between class clown and menace to society.

At school, where he was underachieving, Greaves was “running around setting off fire extinguishers” and acting “like a bit of an idiot,” he said.

Outside of school, he was getting in trouble with the police—at one point arrested on suspicion of theft.

Denzel Greaves training at a Sweet Science boxing session Credit: Luke Whelan

Denzel Greaves training at a Sweet Science boxing session Credit: Luke Whelan

He was on a dangerous trajectory. That was until his school referred him to a boxing project called Sweet Science that gave him a choice between “two paths”, Greaves said.

Leroy Nicholas, head coach of Sweet Science, “came into my life... I would say the ideal time,” Greaves said, now 20 years-old and running his own music studio on the side of a full-time job.

Denzel Greaves training with coach Leroy Nicholas Credit: Luke Whelan

Denzel Greaves training with coach Leroy Nicholas Credit: Luke Whelan

“I think straight away from there, I was ... less time on the streets. More dedicated to putting my time into boxing and kind of bettering myself.”

Similarly, former world champion Anthony Joshua, who trained with Nicholas in 2017, has spoken about how boxing helped him keep out of prison.

The Anthony Joshua Story

In 2009, Joshua was charged by police for “fighting and other crazy stuff”, he told the Songs for Life podcast.

He was remanded for two weeks in Reading prison and then given bail with the requirement of wearing an electronic tag.

After he got bail, Joshua started taking boxing seriously, a sport he had started the same year as the case. But at this point his motivations were far from righteous.

“I thought ‘if I'm going to do a long sentence and I've got these little idiot kids in the jail, I'm going to back myself’,” Joshua told the podcast.

Regardless, this episode was the starting point of Joshua’s career. It led to Joshua spending less time getting into trouble and more time focusing on boxing.

Coach Leroy Nicholas (left) with Anthony Joshua (right) Credit: Sweet Science Boxing

Coach Leroy Nicholas (left) with Anthony Joshua (right) Credit: Sweet Science Boxing

“I became so disciplined when I was on tag. I would be at home by eight o’clock and because I had boxing, I lived the disciplined life," he said.

Thanks to his hard work, Joshua reached the title of British amateur champion at the 2010 GB Championships, and eventually went onto become the world champion we recognise today.

Admittedly, he did have one last hiccup along the way. He was charged with intent to supply class B drugs and was temporarily kicked off the Olympic team, and forced to do community service for a year.

But like Denzel Greaves, boxing gave Anthony Joshua the choice of ‘two paths’ rather than one. It gave him an alternative. Something to focus on that would keep him from getting in trouble.

Since his charge, Anthony Joshua hasn’t been arrested and is widely hailed for his determination and 'boxing spirit'.

However, boxing is more than just a safe space, isolated from the peer pressures and negative influences outside of the gym. It’s what happens in the gym that often makes the difference to people’s lives.

Boxing and mental health

The sport is also praised by those who find relief in hitting a punch bag or stepping into the ring.

Psychologist Dr John Barry from University College London explained: “Some people, especially men, tend to 'act out' stress and uncomfortable feelings such as depression and trauma. Boxing can be a controlled way of doing this.”

The grieving Prince steps in the ring

Prince Harry is someone who has personally found refuge in being able to ‘act out’ like this in the ring.

The Prince told the Telegraph how he used boxing to physically respond to the grief of his mother’s death without resorting to violence.

Harry said that after Princess Diana died in 1997, he was “very close to a complete breakdown on numerous occasions”.

“During those years I took up boxing, because everyone was saying boxing is good for you and it’s a really good way of letting out aggression.”

“And that really saved me because I was on the verge of punching someone, so being able to punch someone who had pads was certainly easier.”

Andy Whitehall from Right Stuff Boxing similarly attributes much of his transformation to boxing. He said how the sport gave him an “acceptable avenue and channel to dissipate a lot of that fear,” caused by his own childhood trauma.

But it’s not only men who’ve experienced the benefits of boxing in helping their mental health through expressing their emotions.

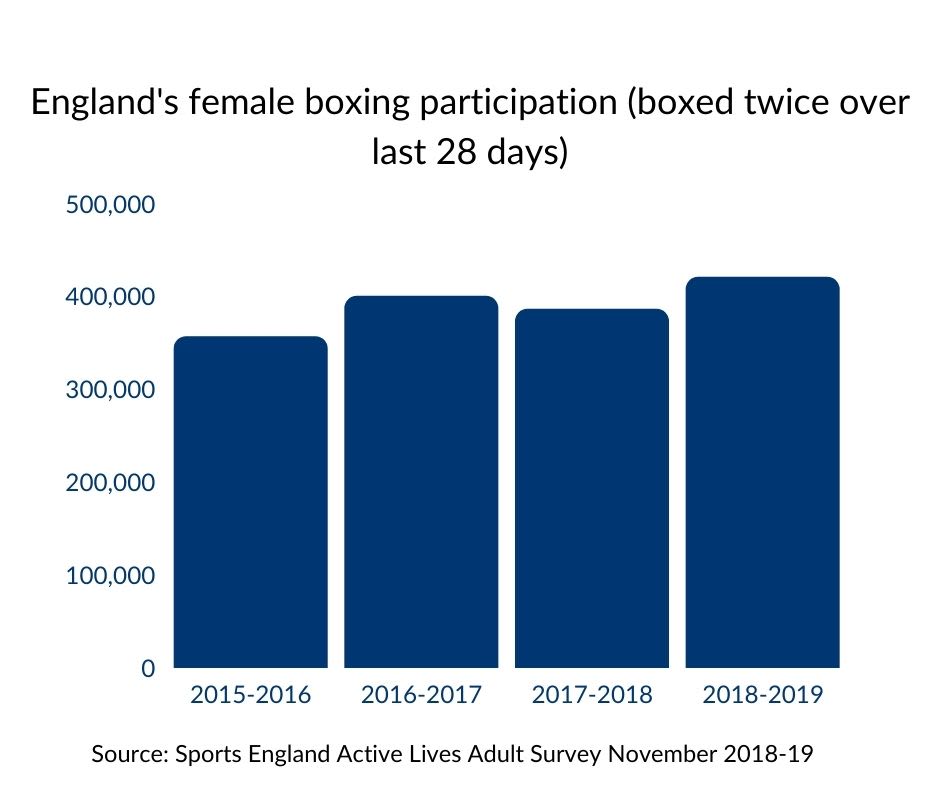

A growing number of women are being introduced to the sport, many of whom are likely to feel the benefits of boxing.

Female boxing participation in England from 2015-2019 (sportengland.org/activelivesapr20)

Female boxing participation in England from 2015-2019 (sportengland.org/activelivesapr20)

The singer Ellie Goulding used boxing classes as an escape from everyday stress, which were causing panic attacks.

The Boxing ring is weirdly the place I feel the most pure & in control. The gold dress represents getting to a place of ultimate power when you have that kind of revaluation about love & forgiveness 💙x https://t.co/kkmv2Vb92L pic.twitter.com/PyUaOu84jL

— Ellie Goulding (@elliegoulding) August 19, 2020

“I started having panic attacks, and the scariest part was it could be triggered by anything. I used to cover my face with a pillow whenever I had to walk outside from the car to the studio”, Ellie told Well+Good.

Boxing was “about seeing and feeling myself get better and stronger... I truly feel that exercise – however you like to work out – is good for the soul,” she said.

But aside from the short term release of endorphins, boxing is often used to create lifelong changes in people.

The perks of having a boxing coach

The one-to-one coaching inherent to the sport can have profound results for self-development. The right coach has the chance to instil discipline, change perceptions and entirely change people’s behaviour.

At Right Stuff Boxing, Whitehall is committed to not just “develop the boxer, but the human being behind it”.

Right Stuff Boxing: A compassionate approach to coaching. Credit: Luke Whelan

Alongside Rocky-esque motivation, Whitehall and his team of mentors—which includes Amy Nolan—use long-term approaches backed by psychotherapists to encourage confidence.

"Andy makes the gym. Andy will speak to every single person in the gym and understand whatever they're going through..."

- Amy Nolan

Coach at Right Stuff Boxing and former pupil

Boxing as psychotherapy

At Right Stuff, one of their approaches of choice is PACE (playfulness, acceptance, curiosity and empathy), coined by US psychologist Dr Dan Hughes.

PACE is mostly used in psychotherapy to help children and parents connect more but can generally improve children’s confidence in relationships after trauma.

It works by reducing young people’s use of ‘coping strategies’ that are caused by traumatic relationships.

These coping behaviours include an ‘avoidance strategy’, whereby young people avoid things that cause them stress or tension, as well as ‘attachment behaviours’ where children become excessively loud to get noticed. In the long-term, they can result in unhealthy relationships and antisocial behaviour.

Whitehall said: “A lot of people misthink of compassion as a weaker thing, which is absolute rubbish as compassion is like one of the strongest emotions you can have.”

Alison Keith, a UK-based practitioner at Hughes' psychotherapy organisation DDP Network, said: “By giving them acceptance and empathy, curiosity and being light and playful at appropriate times can help them to feel safe enough to be in a relationship with you.

“But it takes time. You know, it depends on the level of trauma ... it can take up to three years for the strategies … to start decreasing.

“For children that have lived in trauma, what they've learnt about themselves is that they are 'stupid', 'rubbish', 'useless', 'worthless'.

"And you could only learn something different through having that relationship with someone else over time... Where do you see something different in their eyes, where you learn something different about yourself. Maybe I'm not on this piece of s***. Maybe I am okay.”

Other coaches, such as Danny Spicer, head coach at Epping Forest Amateur Boxing Club, emphasise the importance of "tough love” as a way to build confidence.

Boxing as a school of hard-knocks

Spicer said: “It is a big ask, to get them to get in the ring in front of people and to potentially get hurt. They come out of that ring 10ft taller, though.

It is tough love we give them. We are doing this because we care about them and because we want them to get straight.”

Nicholas from Sweet Science uses hard lessons from his own experiences to develop his boxers, rather than any therapeutic method or approach. The sessions he runs in schools always start with one of his life lessons.

"I've seen a lot of things in my life and I managed to traverse them all without letting them drag me down and learned from them. I take all those things I've learnt and seen to be able to present to these kids.”

- Leroy Nicholas

Head coach at Sweet Science

He said: “I've had a family member who was, you know, got involved in drugs and all the rest of it and ended up losing his life due to that.

“I've got a nephew who, you know, took drugs and lost his life due to that.

"I've seen a lot of things in my life and I managed to traverse them all without letting them drag me down and learned from them. I take all those things I've learnt and seen to be able to present to these kids.”

And he has no shortage of case studies to show the success of his method.

One of his boxers, Valentina Sholaya, 17, described her how his coaching has changed her life.

“Starting in year 7 you would usually find me sitting on one of the small walls, reading with a big book in my hands. Eating my lunch alone, usually.

“I was a loner and I was sort of bullied for it but with boxing I was able to mostly ignore what other people thought of me and feel more comfortable with myself and how I acted and feel more comfortable in my own skin.”

Regardless of the approach, the results are the same: because of boxing young people with more confidence and determination and excitement for life.

The gyms are facing a threat

Dr John Barry said: “Boxing isn't a magic cure for all ills and isn't for everyone.” And no doubt he's correct.

But for a great deal of people, the sport has been transformative. For some it's an antidote to the stresses of everyday life. For others: its a route to complete behaviour change.

Moreover, the impressive range of coaches the sport has to offer, might even be a life-saver for some people who are tortured by their own intolerable trauma.

Yet sadly, the range of benefits community boxing offers is in danger.

Over the lockdowns, a cascade of gyms missed out on months of income which was not replaced with government funding. The sport was excluded from the Conservative government’s list of funded activities.

Some clubs have even resorted to smaller donors who’re dedicated to keeping the clubs alive.

But without the weight of government funding, keeping the gym's afloat is a tricky goal, as Eddie Hearn argues.

So, could another lockdown as a result of the Omicrom variant of Covid-19 be the final blow for the under-funded clubs?

Mickey Helliet of Knock Out Knife Crime, a charity which launched over Covid to fund gyms, summed the issue up to the Hackney Gazette in London: “There can be no doubt that boxing gives young people a focus and discipline that is of benefit to society and can help them to turn their lives around.

“We can’t afford to lose clubs.”

(Photo credits can be found in the caption at the bottom of every photo, except from the scrolling graphics. All images used in the scrolling graphics are credited to Luke Whelan)