Sportswashing: the ugly politics behind the beautiful game

After 12 years of build-up, the Qatar World Cup is finally upon us. “Keep politics out of sport” may be the old adage, but this tournament appears to be sounding its death knell. But what is 'sportswashing' - and why are we only now seeing this phrase cropping up?

Video by James Saunders

Video by James Saunders

As of today, states and state-owned companies own some of Earth's richest football clubs, and sponsor dozens more.

But, if you're a country looking to show yourself off by getting into football, club ownership isn't the only way to do it. You can host a World Cup.

“It’s the most controversial World Cup in history, and a ball hasn’t even been kicked” was Gary Lineker’s opening line in the BBC’s coverage of this year’s tournament in Qatar.

It has been decried by critics as “sportswashing”, and is a lightning rod for argument and vitriol; that's what happens when football and politics come together.

As we'll discover, the term doesn't only refer to football - it has been used to describe certain Olympic Games, too - but with the World Cup in mind, that's the focus.

Key voices: activism, academia and Amnesty International

Peter Tatchell

Peter is a human rights campaigner and director of the Peter Tatchell Foundation, a non-profit human rights awareness organisation. He is famous for his LGBT+ activism, and is the subject of the 2021 Netflix documentary Hating Peter Tatchell. Since the 2008 Beijing Olympics, he has been outspoken on human rights issues in sport.

Photo by Michael Skey

Photo by Michael Skey

Michael Skey

Michael is a senior lecturer in communication and media studies at Loughborough University, with a PhD from the London School of Economics. He is regarded as one of the outstanding voices in academic debates on sportswashing and its definitions.

Neil Durkin

Neil is the media and PR manager (crisis and tactical) at the UK arm of Amnesty International - the world's largest human rights organisation. He has written in HuffPost, featured on BBC News, and is Amnesty UK’s go-to man for questions on sportswashing, the Middle East, Russia and Central Asia.

Vitaly Kazakov

Vitaly is a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Manchester who specialises in sport, media and politics – particularly in Russia. He, and his work, is notable in his field, and he has received media coverage in the BBC, Independent and Huffpost.

What is sportswashing?

"The attempt by regimes and institutions to use sport as a way of glossing over human rights abuses and social injustices"

"An attempt by a nation to rebrand itself using the glamour and the prestige of top tier sport"

"The attempt to use sporting events or sporting clubs to whitewash the reputation of the people who are investing money into it"

"They use sport as a way of distracting attention away from the way they, for example, treat women or they treat minorities"

My four interviews (and interviewees) vary in style and substance, but, helpfully - given that there is no universally accepted definition out there - all agree on some key points.

Peter answers my questions with curt precision. He's time-pressed, and a man in demand during this World Cup; this October, he was on the end of a lot of media coverage after being forced to leave Qatar for protesting against their LGBT+ rights record.

He says: "Sportswashing is the attempt by regimes and institutions to use sport as a way of glossing over human rights abuses and social injustices."

Neil and Vitaly approach the topic from different perspectives - in true campaigner fashion, the former is critical of certain regimes, while the latter, the academic, dives into technicalities, definitions and debates.

Neil says: "Sportswashing, as we define it, roughly, is an attempt by a nation to rebrand itself using the glamour and the prestige of top tier sport."

Vitaly says: "[Sportswashing] refers to the attempt to use sporting events or sporting clubs to whitewash the reputation of the people who are investing money into it."

Michael sits in a middle ground; this is his specialist area, and he speaks on it with detail and care.

In his words, "it focuses on states with, shall we say, problematic human rights or social programmes. And the argument is that they use sport as a way of distracting attention away from the way they, for example, treat women or they treat minorities."

"Rebranding", "whitewashing", "distracting" - these, apparently, are why a country might want to 'sportswash' its reputation. We'll get to exactly what some states are 'washing' later, but first, a crucial question:

Why are we only seeing this term now?

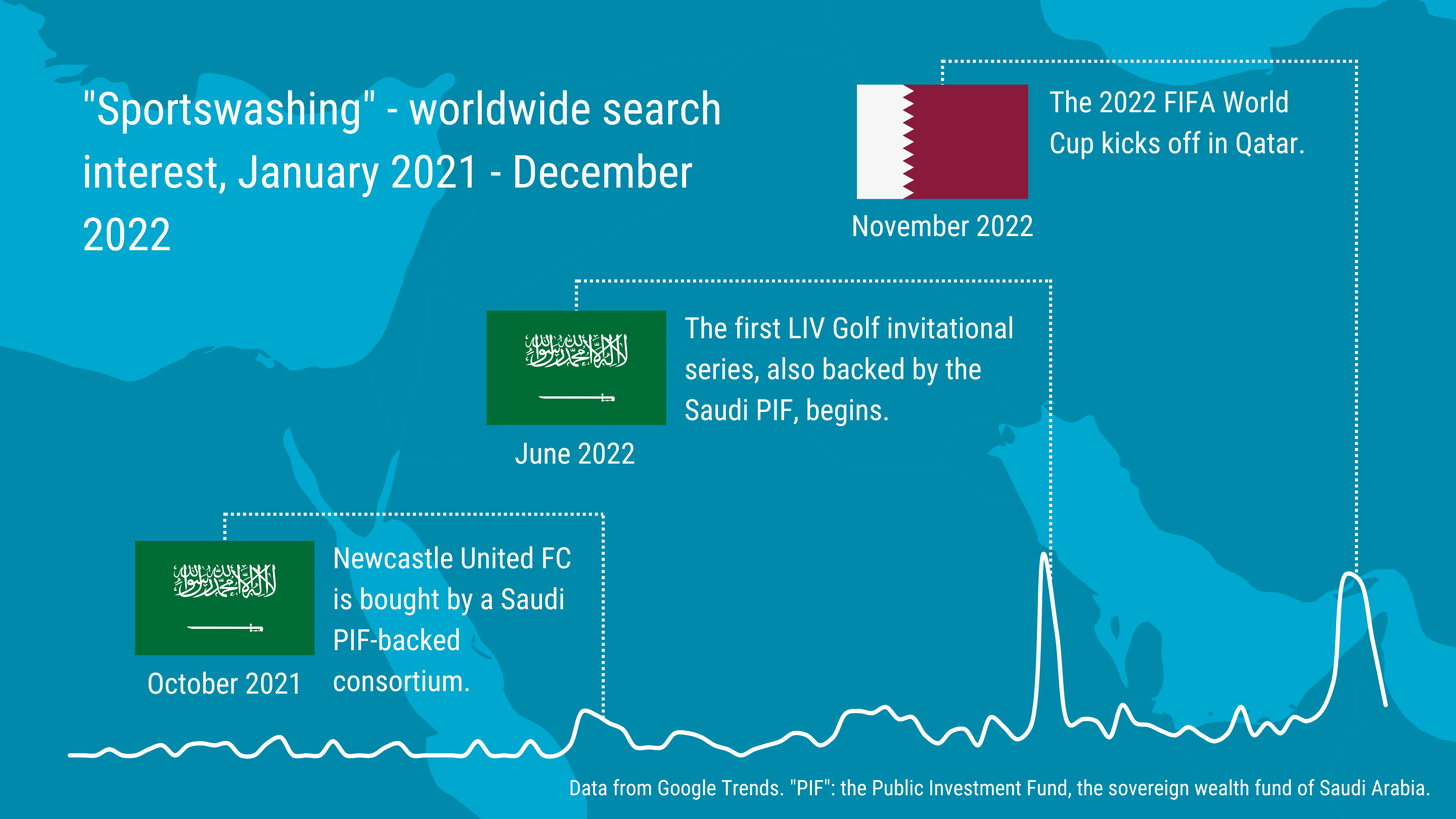

Graphic by James Saunders

Graphic by James Saunders

As the above graphic shows, interest in sportswashing is growing - slowly, sure, but every so often (i.e., when state involvement in football receives media attention) there's a huge spike.

This growth in interest is a recent phenomenon, and Neil points to why. He says: "There's a bit of debate about where the term comes from.

"Certainly, Amnesty didn't invent it. But we have popularised it; we have used it a lot in the last four years or so.

"I think it actually emerged from some kind of PR workshop in Azerbaijan in about 2016 or 2017, when there was an athletics tournament taking place in Azerbaijan - which has got a very poor human rights record."

He says Amnesty started using the term in 2018, but since then, says Neil, "it's really sort of gone into a kind of stellar mode around Saudi Arabia. Not only Saudi Arabia, but they've really taken it to new levels, and they've been piling into so many different sports that it's been hard to ignore".

Michael also covers the origins of the term, and says: "I think most people are probably familiar with whitewashing... an organisation tries to cover up corruption by 'whitewashing' it.

"In the '80s, an environmental campaigner put forward the term ‘greenwashing’ - the way companies tried to cover up a very poor environmental record by putting forward a marketing campaign that said: ‘actually, no, we're wonderful, and our environmental programmes are fantastic’."

The next step on this 'washing'-line, if you will, is sportswashing. Like Neil, Michael says that it has come about in the last three to four years, with the rise of state-run football clubs and the hosting of certain sporting events.

Michael actually shifts the focus toward organisations like Amnesty, saying: "[The term] sportswashing has been used by NGOs, in particular, to try and focus attention on the records of states like Russia and China and the Middle East."

The most recent spike on the graph points to what some may call the most high-profile example of sportswashing in that three-to-four year period: this World Cup.

Miguel Delaney, chief football writer at The Independent, is particularly outspoken on the matter, and attracts a great deal of ire on social media for his views.

While Michael outlined general definitions of sportswashing earlier, he put forward an alternative explanation as to why it's happening now.

A segment of an interview with Michael Skey. Video by James Saunders.

A segment of an interview with Michael Skey. Video by James Saunders.

Who decides what is and isn’t sportswashing?

"We are a democracy, Qatar is a dictatorship. That’s the big difference."

"If you're going to call certain non-Western states 'sportswashers', you have to call European states sportswashers as well."

"The term is used in reference to the ‘bad guys’... whether it's rightfully deserved or not."

A segment of an interview with Vitaly Kazakov. Video by James Saunders.

A segment of an interview with Vitaly Kazakov. Video by James Saunders.

When talking about sportswashing, there's a question that always seems to pop up: why is it sportswashing when countries like Qatar host a World Cup, but not countries like the UK?

Peter says: "It all depends on the severity and scale of the abuses. Obviously, many Western countries are far from perfect, but, unlike Qatar, we don’t yet ban freedom of expression, the right to protest and strike, and we live in a democracy where people can vote to change the government."

Qatar is "not free" according to Freedom House, and in Peter's opinion, "we are a democracy, Qatar is a dictatorship. That’s the big difference".

Michael is keen to point out what some have called 'cognitive dissonance' about the term.

He says: "If you're going to call certain non-Western states 'sportswashers', then you also have to call European states, who are bedevilled by a problematic image, and they [also] use sports in that way – you have to call them sportswashers as well."

"Can Western States sportswash? I think it's fairly obvious that they can... the next World Cup might be a way in which the United States could try and wash its reputation."

Neil says: "If you talk to Saudi officials about sport, they will just simply brush aside questions of sportswashing and say, well, we want to make the country accessible and we think sport is an important way of doing it.

"It isn't necessarily wrong to get involved in sport. The motivations though, we do question. And we do think it is about trying to deflect and drag attention away from the things that we would like people to be talking about."

Vitaly highlights what is perhaps the key point. He says: "The term is used in reference to the ‘bad guys’, or the illiberal regimes, or people with negative reputations - whether it's rightfully deserved or not."

It seems, then, that virtue - in the world of sportswashing - is in the eye of the beholder. I reached out to the embassies of Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE for comment about how they perceived sportswashing. I received no response.

Why is it important to talk about this? Why now?

Out of 32 countries participating in the 2022 World Cup, 24 do not criminalise LGBT+ people. This includes all European, North and South American teams as well as Australia, Japan and South Korea. It's the majority, but a third of this edition's competitors still exhibit homophobic laws, according to the Human Dignity Trust (HDT).

The HDT states that all five African countries at this World Cup - Cameroon, Ghana, Morocco, Senegal and Tunisia - criminalise LGBT+ people, and impose a maximum of three years' imprisonment for sex between men. Out of the five, only Ghana has no legal restrictions on sex between women.

The HDT also specifies that all three Middle Eastern countries at this World Cup - Iran, Saudi Arabia and hosts Qatar - criminalise LGBT+ people, and impose a maximum punishment of the death penalty for sexual activity between members of the same sex. Saudi Arabia expressly criminalises the gender expression of trans people, and Qatar permits death by stoning as its maximum sentence.

England, Wales, Belgium, Switzerland, Germany and Denmark all joined the Netherlands' initiative for their captains to wear the 'OneLove' armband to raise awareness over LGBT+ rights issues in Qatar. All seven countries then opted not to wear it after being threatened with 'sporting sanctions' by FIFA.

All participating nations (including England and Wales, as part of the UK) are UN member states, and are legally obliged to uphold the values of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and protect LGBT+ people. But some do not - including this year's host country and Saudi Arabia, a potential co-host of the 2030 tournament.

Fundamentally, the word sportswashing itself implies there's something to clean up - reputations, images and, like what Peter campaigns against, poor rights records.

Peter thinks we should judge Qatar on the basis of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and says: "I don’t agree with imposing Western values on other countries, but I do support holding them to account for violating international human rights law."

"Hosting a major sporting event like the World Cup or the Olympics is a privilege, not a right. With that privilege goes the responsibility to uphold the human rights values that are enshrined in FIFA’s own statutes."

"FIFA has to secure cast-iron commitments to upholding human rights by all the competing nations. This includes a pledge that they will not discriminate against a gay footballer. If nations cannot give those guarantees, they should be barred from competing in the World Cup."

Vitaly notes that the World Cup can actually increase, rather than distract, attention. He says: "It obviously puts a spotlight on to the host states and issues that may not have been discussed. Otherwise, in terms of the human rights records, the lives of migrant workers and so on wouldn't have been in focus at all.

"FIFA has to secure cast-iron commitments to upholding human rights by all the competing nations... If nations cannot give those guarantees, they should be barred from competing in the World Cup"

The OneLove campaign attracted significant criticism, especially after the teams who wanted to wear the armband were knocked out of the competition.

A segment of an interview with Peter Tatchell. Video by James Saunders.

A segment of an interview with Peter Tatchell. Video by James Saunders.

Whose job is it to combat sportswashing?

Much has been said about nations and organisations, but little about the fans. Should we be expecting them to do more, to protest and to fight back, or is it too much responsibility for groups with ever-decreasing sway in football's big decisions?

"Fans can, should and often do protest"

Peter says the fans aren't responsible for what happens at the highest echelons of football.

He says: "Of course, fans can, should and often do protest, however, their protest doesn’t have the financial leverage of the billionaire backers.

"Football has become far too much a big business driven by commercial interests rather than the wishes of the fans.

"There’s not a lot the fans can do apart from join protests and stay away from matches, but that is a very big ask for passionate die-hard supporters.

"Some have chosen to go to matches and hold up signs condemning club takeovers and collusion with human rights abusers. That’s good, it’s effective, and I would encourage more of it.

Vitaly says: "We shouldn't be blaming the fans, you know, they just remain loyal supporters of the club; sticking with it through the lows and the highs, and if the highs are problematic, the fans shouldn't be to blame."

Michael says: "If you're born and brought up in somewhere like Newcastle, and Saudi Arabia buys your team and makes them good again, do we have a right to say no, you have to stay away from the ground? I don't think we do.

Neil says: "We don't want to guilt trip fans over this. We're not saying 'stop supporting your club because this particular ownership group have now taken control'.

"We've said, you know, carry on supporting your club - by all means, that's your affair - but do look seriously at what we've said, and what others are saying.

"In the end, the primary focus is on states... It really isn't about guilt-tripping fans"

A segment of an interview with Neil Durkin. Video by James Saunders.

A segment of an interview with Neil Durkin. Video by James Saunders.

Is sportswashing here to stay?

Vitaly says: "I think this issue is here to stay. And, of course, it's a matter of how we as a society – regulators, leaders on the political sides, the experts who investigate it and how they deal with it – will improve and evolve as time goes on.

Michael says: "People will carry on talking about sportswashing in the media, for example. It's a very handy term to use. I think the media like it.

"I think for the foreseeable future, it will be something that is within popular media discourse. It'll continue to be used because it's a nice shorthand - but whether it gets used in relation to Western states, I don't know.

"I mean, that will be quite interesting to see - if, at the next World Cup, America will be accused of sportswashing.

"I doubt it."