Six Nations: Is Rugby Union Safe?

With the Six Nations fast approaching and concussion injuries on the rise, Jonathan Moynihan explores whether rugby union is safe.

Francesco Celot, 40, a sales manager working in construction, has recently recovered from a head injury after playing in his team’s first match of the season.

He got hit side-on behind his ear accidentally in the first game of his year by somebody from his team as the player came in from behind.

The loosehead or hooker by trade felt a bit strange afterwards because he felt that it wasn’t a definite concussion.

Later though, he began to feel confused, so he came off at half-time. He realised that he had issues with his eyesight, lights, and his balance after the incident.

Celot said that the concussion took four weeks to recover from. He was forced to take time off work because a simple task would take ten times longer than usual.

Celot’s concussion story is increasingly common in both amateur and professional rugby union.

Raynes Park Sports Ground: London Media in huddle ©️JonathanMoynihan

Raynes Park Sports Ground: London Media in huddle ©️JonathanMoynihan

Raynes Park Sports Ground: maul in game ©️JonathanMoynihan

Raynes Park Sports Ground: maul in game ©️JonathanMoynihan

Raynes Park Sports Ground: ball on pitch ©️JonathanMoynihan

Raynes Park Sports Ground: ball on pitch ©️JonathanMoynihan

What is concussion?

Concussion “is a traumatic brain injury typically resulting from a blow to the head or body, which results in forces being transmitted to the brain. The symptoms can present immediately and be short-lived, or the onset of symptoms may be delayed and start to occur some time after the initial injury,” according to England Rugby.

Hamish Bain, 29, a neurologist at University College Hospital, said: “Within seconds, direct trauma to the skull can cause bleeding at the site of contusion (essentially a brain bruise) and is often accompanied by damage to the opposite side of the brain.

“Bleeding disrupts the delivery of oxygen to this area and releases neurotoxic chemicals that can cause damage locally.

“In hours to days, the lack of blood flow and consumption of resources can cause your brain function to be impaired for several days while the damage is repaired.

“In this period, your brain is highly vulnerable to a second impact that will make total recovery time significantly longer.”

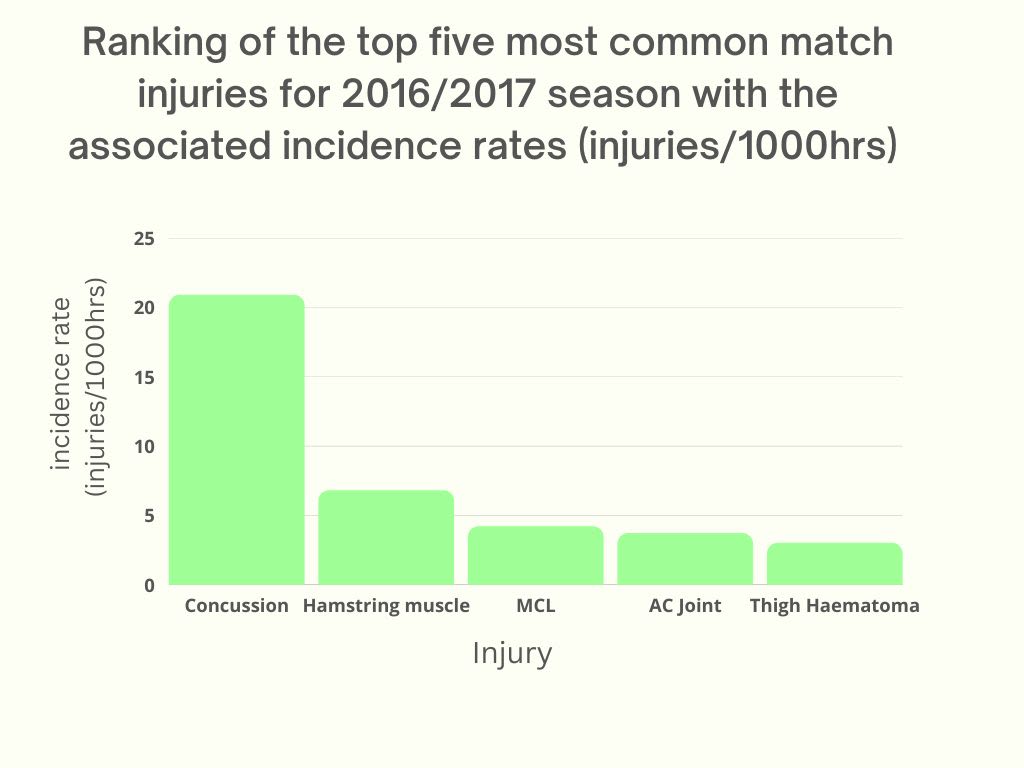

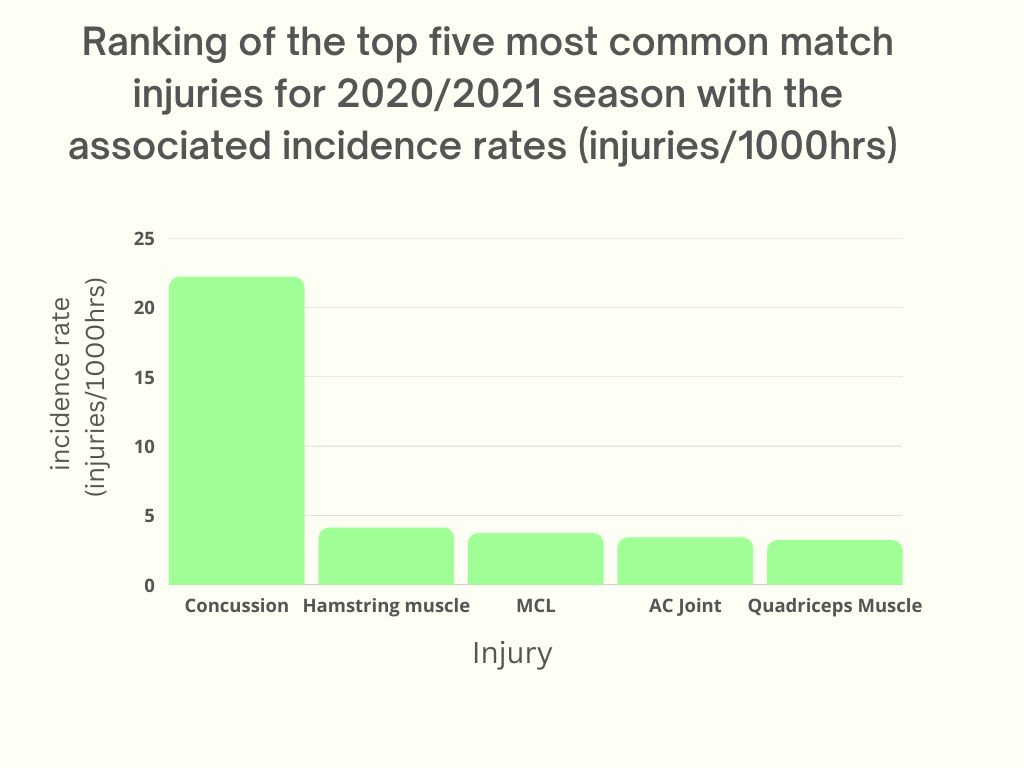

The statistics on concussion are stark, even in England Rugby’s own studies. There has been an increase in the incidence of concussions in the professional game documented by the England Professional Rugby Injury Surveillance Project season report 2020/2021, which found that the most common injury was a concussion for the tenth season in a row. Concussion accounted for 28% of all injuries in the professional game in that season.

Players spent an average of 17 days off with a concussion in 2020/21 compared to the average of 13 days per concussion between 2002 and 2020, showing the severity of concussions has increased as players are spending more time on the sidelines needing to recover.

Independent studies conducted by academics back the upsurge in concussion in the professional game. In the British Journal of Sports Medicine, a study collected data from the four Welsh professional teams – Cardiff Blues, Dragons, Ospreys, and Scarlets- as well as the Welsh men’s international team.

Rafferty et al found that between the seasons of 2012/13 and 2015/16, concussions grew across the four seasons that they researched.

Alongside the fact that concussion was increasing, the study documented that there is a 38% higher injury risk after having a concussion.

Rules and Legislation

In order to protect players from the dangers of concussion, the authority in charge of governing rugby, World Rugby, introduced the Head Injury Assessment (HIA) back in August 2015, otherwise known as HIAs in common rugby slang.

The HIA allows for the team of the player who may have been concussed to make a substitution so that the player can take tests to determine whether he or she has a concussion.

The HIA is a three-part process where the player is seen by either a match official, the doctor for the team and the independent doctor for the match. There is then an off-field review using an assessment tool, a pitch-side video review, and a review by a doctor.

This is followed by another assessment inside three hours of the game being completed. It is used to decide whether there has been any improvement in the player’s condition using the test used in the previous part.

Finally, the last stage, three happens in the next two or three days. A doctor assesses the player and the same test as before to see if the player’s cognitive ability has improved.

However, the HIA is not a foolproof system to protect players from concussion, as seen in the recent case of Nic White, the Australian scrum-half, during an Autumn Nations Series game against Ireland.

White, 32, played on despite having a head injury in the game because of “discrepancies around process and communication,” according to an independent review.

The review found that he should have been substituted, even though he had already passed an HIA.

If players get concussed and cannot play on, they have to undergo the return-to-play protocol, which involves 14 days of rest and recovery followed by a slow return to full-contact rugby spread over time.

The return-to-play protocol is a process that involves the player increasing his workload from light exercise to full contact training over a period of five days if it is quick, but it can be much slower if the symptoms of concussion continue to appear during the process.

Sometimes professional rugby players do not ever come back from the return-to-play protocols, such as George Taylor, an Edinburgh Rugby player, who was forced to retire due to concussion at the start of this year.

Source: England Professional Rugby Injury Surveillance Project season report 2020/2021

Source: England Professional Rugby Injury Surveillance Project season report 2020/2021

Source: England Professional Rugby Injury Surveillance Project season report 2020/2021

Source: England Professional Rugby Injury Surveillance Project season report 2020/2021

Is enough being done to combat concussion?

Notwithstanding the HIA and the return-to-play protocols, it can be argued that there has not been enough done to combat concussion in the past and the present.

Given the lack of knowledge about concussion in the past, it has led to a number of former players, including Steve Thompson, the 2003 World Cup winning hooker, to join class action lawsuits against their respective unions and World Rugby because they feel that the unions did not safeguard them from concussions and sub-concussive hits in the past.

It has led to several players revealing that they have been diagnosed with dementia at a very young age, such as Ryan Jones, who was diagnosed at 41.

It is not just historically that players are beginning to feel the repercussions of concussions as players like David Denton, the former Scotland no8, had to stop playing entirely because of a seemingly innocuous head injury during a game against Northampton Saints in October 2018.

Tim Stimpson, 49, a former England international who is now part of Progressive Rugby, said: “Unquestionably more can and has to be done [to combat concussion]. That’s why we produced out seven-point player welfare plan for the elite game.

“It’s great to see that World Rugby and others are doing research, but until they have results, we strongly believe they have a duty to err on the side of caution, and that means undertaking tangible actions like extending the return to play period further and holding clubs/nations to account when they fail in their duty to protect players.”

Progressive Rugby is a non-profit group made up of medics, academics, and former professional rugby players, whose aim is to make sure players are protected as much as possible to make the game continue to grow.

Sam Graham, 25, a Northampton Saints player, said: “I think if you go back maybe 10 years, even only 10 years. I think head injuries or brain injuries and concussions weren’t really spoken about as much.

“It all looked pretty awful on TV and people would discuss it them but you know, rugby has always been deemed as this real tough person sport that you know, as long as you're not dead you just carry on.

“I'm glad that that message is kind of changing and has been taken a little more seriously.”

Do contact sports have an inherent risk?

With more and more players revealing they have early-onset dementia or retiring earlier after taking several concussions, it has meant there has been a debate about whether rugby union is safe to play with its current laws and rules.

Stimpson said: “All contact sports – and indeed many things in life - carry an element of risk and rugby is no different.

“It’s about making sure that risk is as low as possible and having the information so you can make an informed decision as a player or a parent.

“I allow my boys to play and of course wouldn’t do that unless I believed it was safe for them to do so.”

Meanwhile, Bain said: “The short answer is that it’s not really…

“It's just we need to be much more transparent with the degree and severity of some of these injuries.

“And I think what's really important is taking players off the pitch, if there's a kind of any suspicion of concussion, which is actually very difficult thing to evaluate.

“But I think it's really important, you get trained professionals to do these evaluations.”

Thus, would Celot still play if he had a severe concussion?

The answer would be no because it would affect him for the rest of his life.

The Rugby Football Union (RFU), World Rugby, Premiership Rugby and the Rugby Players Association (RPA) did not respond to comment.

All photos were taken by Jonathan Moynihan.

Raynes Park Sports Ground: teams prepare for a scrum ©️JonathanMoynihan

Raynes Park Sports Ground: teams prepare for a scrum ©️JonathanMoynihan

Raynes Park Sports Ground: London Media scrum half passing ©️JonathanMoynihan

Raynes Park Sports Ground: London Media scrum half passing ©️JonathanMoynihan

Raynes Park Sports Ground: medical bag ©️JonathanMoynihan

Raynes Park Sports Ground: medical bag ©️JonathanMoynihan

For more information on head injuries, click on this link.