Language Personalities

Do you feel like a different person when you speak a different language?

Growing up, I was met with confusion if I spoke to one parent in the wrong language. Not because they didn't understand what I was saying, but because my parents were insistent on us growing up bilingual, retaining both English and Italian. I remember one day asking my Dad something and he replied, 'cosa?' so I repeated myself only for him to say it again, 'cosa?'. This went on for enough times until I realised he knew perfectly well what I was saying. He just wanted me to say it in Italian. However frustrating it may have been at the time, I will always be grateful.

It was around this point where my first language, Italian, slowly took the passenger seat and English became my day-to-day language. Without knowing it, I split in two.

What I’ve noticed is when I switch languages, from English to Italian, my voice drops a good few decibels, my facial expressions change, and I feel different. Hear for yourself;

As a language, Italian lets you say so much with so little, where 50% of a conversation may just be body language and the rest is a string of rich and thoughtful words or sayings. A few favourites include the name of the cult classic, Tiramisu, which translates to 'pull me up', a nod to the consequences of it's star ingredient; caffeine.

Another one you may or may not have heard of, but is a favourite of mine, is when you use bread to wipe up the leftover sauce on your plate, it's called 'fare la scarpetta' or 'doing the little shoe', referencing the shoe-like form the bread takes when you squeeze it together.

Maybe more importantly, it's when you sit down for dinner and are met with an echoed, 'Buon Appetito'. This stands as one of the earliest social norms I learned, from sitting at my Nonna and Nonno's teal kitchen table through to its interchangeable use as a lunch or dinner time goodbye, replacing 'ciao' by wishing someone a good meal instead.

All of these little details, they disappear in English. And with it goes this other feeling, a different part of me that sits, waiting for the next time I can speak Italian again.

The best way to describe it is a 'language personality'. A shift in how you feel and how you act based on the language you are speaking. So, do other's feel the same and is there any real scientific merit to this feeling?

Dr JANET GEIPEL

German - English - Italian

Dr Janet Geipel is from Germany and learned English in school and Italian through friends when she lived in Italy. Shifting languages frequently and raising her daughter in a bilingual household, she describes a sense of never truly being herself when she isn't speaking German. Through the way she can communicate her feelings to the way she can express humour, there's a shift she finds difficult to describe.

One example is communicating love. In English, you can say 'I love you' to a partner, a parent, or a friend and the way you say it will imply different things. It can be casual and a statement of care as well as something deeper. Meanwhile, in German, the direct translation 'Ich Liebe dich' means something very different. It is not used casually, rather, it's very profound. Instead, you use 'Ich hab dich lieb' which can only be described as saying I have care for your, I have love for you. Her bilingual daughter, however, translates it all the same.

XXX

“[In German] I can be ironic, I can be funny. I feel some people don't know me really, in the UK or in Italy, because they can't understand how funny I am in my native tongue. The moment I come home and I have my siblings around and we throw simple words around in such a funny way. You can't do this in your foreign language unless you are extraordinarily proficient. It's just not the same. So I do feel very different because I can use the language in a very different way. I can be funny suddenly and, yeah.”

ANJUM PEERBACOS

Urdu - English

Anjum grew up in London, learning Urdu from her mother and English at school. When switching between languages she describes a shift in the way her self - perception as well as how the language's culture influences the way she can express herself.

XX

“I just think that I'm just, just that bit more edgy in Urdu than I am probably in English. I think in English also there's an element of this British culture which is always, to some extent, the stiff upper lip."

"Urdu is much more poetic as a language. It's much more, in some ways, attuned emotionally and you definitely would express how you're feeling and there wouldn't be any reserve in terms of your emotional reaction to something. For example, so, I know we say it, you might say it in Shakespearean English like, 'oh, woe is me', that kind of thing. You wouldn't have that now in 21st century vernacular. But in Urdu it's very much like, 'aye hi', like 'what's happened'? It's a very expressive language and I don't think you always have the equivalent in English because it's linked to a particular culture."

HECTOR DE GALARD TERRAUBE

French - English

Hector grew up speaking French at home while studying in English for most of his life. He explains how switching languages impacts his perception of how he sounds as well as how he feels speaking to different social groups such as family vs his friends.

“I do feel a difference. I don't think the difference is huge, like I don't change based on the language I'm speaking but there are some differences that I know for a fact. Like some of them also have to do with the pitch of my voice and the way I feel like I sound when I speak the language. My voice can be a little deeper in French than in English.”

“Since I've studied in English most of my life, I definitely think I feel a bit more, intellectual and well-spoken sometimes when it comes to English, especially when it comes to like intellectual subjects, just because that's something I've always done. But I also feel a lot more comfortable speaking to people my age in English, because a lot of my friends were English when I was growing up."

"In French, I feel like I'm super polite and I'm really good at finding my words when I'm trying to make a good impression to someone that might be a bit older than me, whether it's like a grandparent or parents or a friend, and I don't feel like myself when I'm speaking in French to people that are my age and I'm trying to be kind of you know cool and put some slang and everything, I don't feel myself whereas in English I definitely do feel myself."

ELISE DOROTHEA

Norwegian - English - French

Elise is from Norway and now lives in the UK. Learning English at school from the age of six, Elise talks about how learning English in a classroom setting meant she has had to adjust how to sound her age, picking up colloquialisms that the 'Queen's English' does not have. Having also learnt French and spending a year in France, she discusses how each language comes with an entirely different face.

X

“I say 'that's nice' in English a lot, to the point of this doesn't even make sense. It's like, 'oh that's nice', but in Norwegian, I would have had so many different variations of nice to describe something, which I feel like there's no equivalent in English.”

"You can't show the full extent of your humour and the way you would play with the language, which you know really well, and have all the cultural connotations with and all those things. It's sort of weird trying to bring your personality from one language into a different language because you can't translate everything word for word in that way."

So, why do we feel this way?

This is what the research says

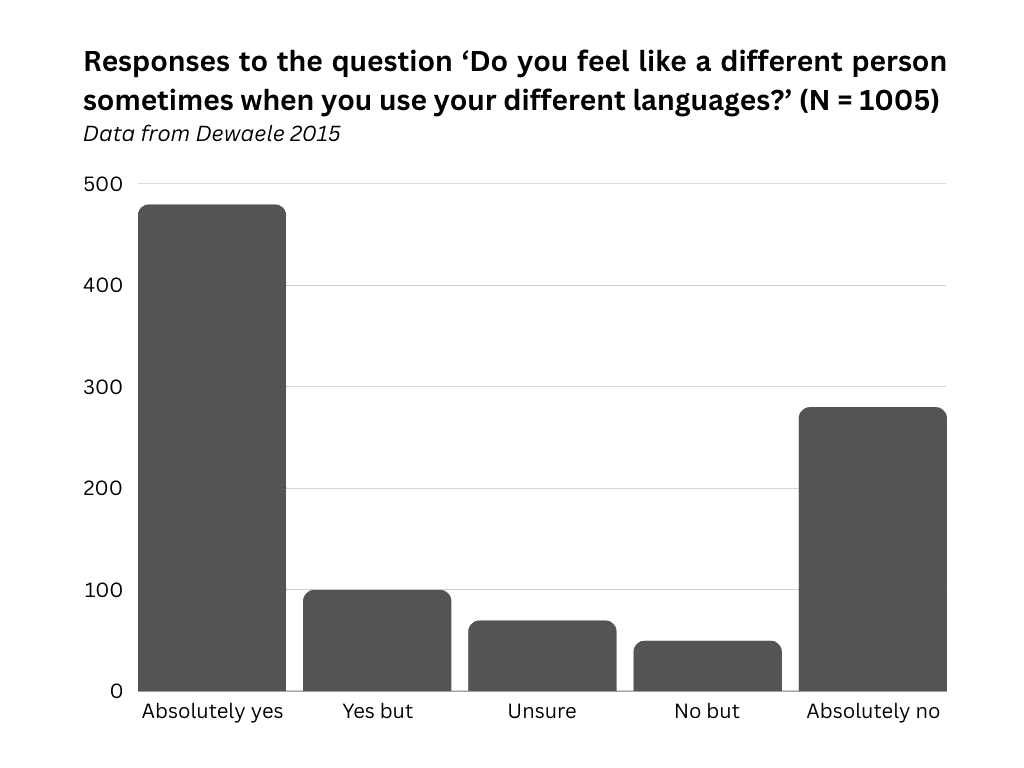

Around 80% of bilingual and multilingual speakers describe feeling like a different person when they switch languages, according to research by Dr Jean-Marc Dewaele, professor in Applied Linguistics & Multilingualism at Birkbeck University of London.

This, however, is a change in self-perception, says Dr Dewaele, where people perceive themselves to be different when they are just adjusting to the language’s cultural convention.

He explains using the example of a Finnish-Italian bilingual. Italians tend to use a lot of hand gestures when speaking compared to Finns. In this case, when you switch language, from Finnish into Italian, you are likely to start using your hands more and maybe come across as more extroverted and louder.

Rather than your personality changing you are making a mental shift into Italian cultural and social norms.

“Using a particular language, or switching to a particular language, activates the cultural knowledge linked to that language. And that includes rules of communication, like how loud will you speak? Will you wait until your interlocutor stops before saying something? Or will you interrupt the interlocutor, which is okay in one culture and not okay in another culture?”

"People have the same personality, whatever language they speak....What varies is the perception you have of your personality and the perception you have of your typical behaviour when you use a particular language.”

Accommodation Theory Explained

This behavioural change is not exclusive to languages. In fact, we do it all the time in what can be explained through Accommodation theory; the shift or change in behaviours based on the social context we surround ourselves with.

Dr Ursula Kania, a senior lecturer in English Language at the University of Liverpool said: “If we're in very formal situations we use language differently and we might even feel that we have a work personality and a home personality.”

One way to think about it is a gear shift. At home, you might be in first gear and express a ‘home personality’, while at work you might switch into second gear and express a ‘work personality’. Switching languages could be seen as jumping from first gear into fifth. The car has, in all its technicalities, stayed the same but the adjustment you have to make to switch gears and the impact that has, feels drastic. Like a whole new ‘personality’.

Dr Kania said: “With bilinguals and multilinguals, the situation is kind of heightened because usually we don't switch from one dialect to the other, but we switch from one language to the other. So it's a more pronounced shift quite often because usually we're dealing not just with different linguistic contexts but also with different cultural contexts. And that, of course can also bring with it this heightened sense of oh, I'm actually a different person now. This is usually what culture does with us as well. It shapes our personalities."

Dr Kania added: “People kind of switch gears in a more pronounced way when they switch from one language to the other.”

This ‘gear shift’, however, comes with adjustments in our behaviour too. From decision making to the way we feel about ourselves, research has found a significant change in our behaviour based on which language you are using. This is known as the foreign language effect.

The Foreign Language Effect Explained

Astudy was conducted in Hong Kong at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic by Dr Janet Geipel, lecturer in Behavioural Science at Exeter University, to assess the impact of language in bilinguals when making health decisions.

The study assessed bilingual Cantonese-English participants by presenting COVID-19 vaccine information and its risks.

The study found that people trusted the information more when it was presented in their foreign language, English, than when it was presented in Cantonese.

These results have been replicated across various scenarios showing people are more open to taking risks, breaking social norms or making moral judgements in their foreign language while feeling more logical and emotional in their native language.

Academics, such as Dr Geipel and Dr Dewaele, explain that this is because of how we learn our first language. Its implicit during our childhood where we absorb not just the words, but a range of social cues such as facial expressions, tone and social contexts. This builds up a series of emotional connotations to those words and experiences which explains why we can detach more easily in our foreign language.

The way our languages influence us, from self expression, self perception to our decision making, changes constantly, varying from person to person with no one size fits all.

This amalgamation of childhood memories, emotions, linguistic and cultural norms all feed into one another to shape this unique relationship between ourselves and our languages.

So, although in an academic sense the idea of a 'language personality' doesn't technically exist, that feeling and experience ultimately does.

As I’ve got older, I’ve tried to bring my ‘language personalities’ together. From teaching friends phrases or words, bringing in gestures into English-speaking contexts, or in English referring to my Italian 'grandmother' as what I actually know her as, my Nonna. All of these small things may sound insignificant but have found that it always makes me feel that bit more connected to both 'sides' of who I am.

Baby steps!