Journeymen:

the best-kept secret in boxing

Meet the professional fighters

who choose to lose for a living

Mickey Cunningham leans over the ropes and chats casually to his team. His body is sinewy in that knotty, angry kind of way, but when he turns to the camera, he looks happy and relaxed.

The fighter across the ring is younger, possibly by as many as 20 years. He doesn’t smile as he greets the crowd. Instead, he jumps on the spot with a jittery energy.

The two men meet in the centre of the ring and as the first round begins, it quickly becomes clear who is the better boxer. Mickey evades punches easily and dances around the canvas. He feints, slips and rolls with startlingly quick reflexes, and even the layman can see that he’s extraordinarily skilled.

When the winner is announced, however, it’s the younger boxer whose name is called out.

Confused, I pause the video on YouTube and scroll to the comments. One catches my eye.

I agree. Mickey usually throws more punches – a fact I know well, given that he’s my own boxing coach. I see that he has replied to the comment. It reads: “Hey amigo! That was my 1st ever fight as a journeyman."

When I next see Mickey, I ask him what this means – and so begins my initiation into the world of the journeyman, where mercenary boxers are paid to lose and men are broken in more ways than one.

What is a journeyman?

In the crudest terms, a journeyman is a boxer who is paid to lose, but very few people would put it so bluntly. Instead, they may refer to an “opponent” or “away fighter”, who is hired to make an up-and-coming boxer look good.

This up-and-coming boxer – known as the “prospect” or “home fighter” – pays for the journeyman from his own pocket.

The optics may be damning, but using journeymen isn’t “match fixing” as most of us understand it, nor is it choreographed like professional wrestling. The bloodied noses and broken bones are very much real.

Johnny Greaves (left), one of the UK's most famous journeymen (c. David Davies/Alamy)

Johnny Greaves (left), one of the UK's most famous journeymen (c. David Davies/Alamy)

To understand the role of journeymen, we have to go back to the 80s when small hall boxing was booming. These matches – which took place in leisure centres, community halls and other unglamorous venues – would draw sizeable crowds. However, as audiences moved from local entertainment in the form of sports, theatre and cinema to home entertainment, the demand for small hall boxing dwindled.

Promoters began to rely on the boxers themselves to attract a crowd. The fighters who could do this successfully were known as the “ticket sellers” – and it was bad for business when a ticket seller lost. His audience was unlikely to turn up to watch him again, and so began the demand for “opponents”, other fighters who would give the crowd a good show and not test the ticket seller too hard.

These opponents came to be known as journeymen, skilled boxers who spent a lot of time on the road to face boxers on their home turf to a hostile crowd.

By the mid-90s, as Sky TV and pay-per-view swallowed most of the money in the sport, small hall boxing increasingly relied on ticket sellers for its very survival.

Mark Turley, the author of Journeymen: The Other Side of the Boxing Business, likens the practice in his book to a 16-year-old Wayne Rooney being told that he can play only if he sells a few hundred tickets to his pals. Failing that, his place will go to a less-skilled footballer who can bring in a crowd.

This is essentially what happens in boxing. If a promising young boxer can’t sell tickets, then he has two options: quit the sport or become a journeyman.

Small hall boxing came under threat (c. Atelier Joly/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Small hall boxing came under threat (c. Atelier Joly/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Small hall boxing came under threat (c. VVShots/Dreamstime)

Small hall boxing came under threat (c. VVShots/Dreamstime)

Small hall boxing came under threat (c. Jbanham91/CC BY-SA 4.0)

Small hall boxing came under threat (c. Jbanham91/CC BY-SA 4.0)

Journeymen show you the ropes, says Duke McKenzie MBE (c. Kia Abdullah)

Journeymen show you the ropes, says Duke McKenzie MBE (c. Kia Abdullah)

The role of a journeyman

Unlike prospects, who may fight two to three times a year, journeymen tend to fight two, three or four times a month. The British Boxing Board of Control (BBBoC) doesn’t allow fighters to compete more than once a week.

A journeyman’s record will be shocking to the untrained eye – surely, anyone that bad shouldn’t be allowed to fight – but insiders understand that journeymen are not technically bad. In fact, they are usually highly skilled and can often beat the prospect in a fair match, but that is not their role.

Journeymen give the crowd what it wants, but there’s more to the role. They educate young prospects, get them ready for the big leagues and help them build a flawless record.

Turley explains: “If you go back to the old days of boxing, defeats were common. You would get guys that had had 30 fights and lost half of them and still won titles because it wasn't considered such a blemish on your record to lose. It was part of the learning process, but in modern boxing, it is really frowned upon. That's what creates the incentive to have this system.”

As such, most prospects’ string of early wins is likely to feature a few journeymen. These fights, however, aren’t necessarily easy, says Duke McKenzie MBE, former three-weight world champion.

He says: “Journeymen show you the ropes. They show you what it is to be pulled around, tied up, held on, pushed back, hit low. They may thumb you in the eye, pull your head down, step on your foot, give you plenty to think about. You've got to work out that puzzle as the rounds go on.”

In this way, prospects learn their trade while building up the sort of record demanded by TV.

Mickey Helliet, a manager and promoter, says that a televised fight between two undefeated boxers is a much greater pull.

He tells me: “If we can get a boxer a record of 15 fights, 15 wins, television will probably develop an interest to broadcast his fights. To the uneducated viewer – which the majority of the viewers are – he’s had 15 fights and he's won them all.”

An undefeated record is more likely to open doors (c. Kia Abdullah)

An undefeated record is more likely to open doors (c. Kia Abdullah)

An open secret

When Turley published Journeymen, some insiders were unhappy that he had revealed to the public what was an open secret within the trade.

He tells me: “There was a bit of a veil of silence drawn over it and I did get some kickback on that. I had a few boxing figures that weren't very happy with me after I wrote the book. One person threatened to sue me. Someone else threatened to come round and beat me up.”

Although the practice is more widely discussed now, the majority of fans are unlikely to know the truth.

Turley explains: “The idea is that the audience don't know because otherwise why would they buy tickets? If they're going to spend 40 quid to go and see someone at York Hall and they know they're going to win, it's pointless, so you have to maintain – or try to maintain – that pretense that it's real.”

Betting isn’t an issue as the odds are heavily stacked in favour of the prospect, so there is little legal impetus to change the system.

The BBBoC does call in fighters with heavy losses on their record, but Turley says this is just a way to keep up appearances.

“They know full well how all this stuff works, but they can't be seen to ratify that publicly. They can't say, ‘well, we know that boxers are losing on purpose’ and so they pretend that they're not,” says Turley.

The BBBoC did not respond to requests for comment.

Journeymen provide training for up-and-coming boxers (c. Kia Abdullah)

Journeymen provide training for up-and-coming boxers (c. Kia Abdullah)

The journeymen

Clearly, the system benefits prospects, managers, promoters, viewers and television executives – but what about the journeymen? Can they succeed in a system which forces them to lose?

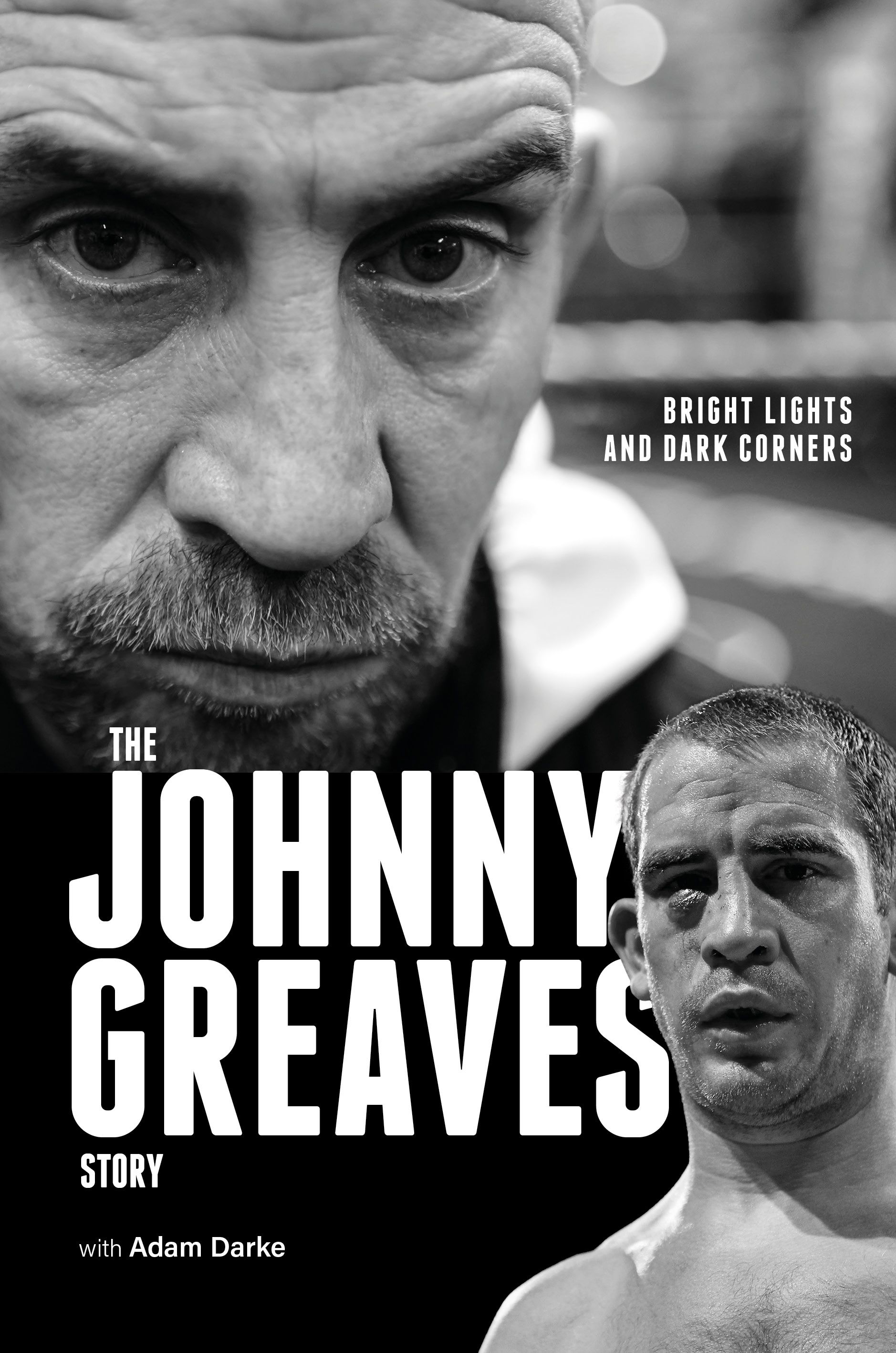

Johnny Greaves, 46, a famous former journeyman and author of Bright Lights and Dark Corners, believes they can.

Between the years of 2007 and 2013, Greaves had 100 professional fights, losing 96 of them.

While prospects train for a match for months, Greaves once took a fight at an hour’s notice. He had to borrow a friend’s gumshield and lost his two front teeth as a result.

Greaves tells me: “I turned pro to put food on the table. Winning wouldn't put food on the table, so I decided to do things the way I did.”

At £1,000 to £1,500 per fight, a journeyman generally takes home more cash than he might do as a prospect. In fact, by the time a prospect pays a cut to his manager, promoter and the venue, as well as the journeyman, he may end up fighting for nothing.

Greaves primarily fought for money but he also loved to fight. He tells me: “I grew up in Upton Park. I was fighting weekly anyway. I loved to scrap, so to be getting paid, I loved it.”

Johnny Greaves' autobiography (c. Johnny Greaves)

Johnny Greaves' autobiography (c. Johnny Greaves)

Having read Greaves’ book, I wonder if there is also an element of masochism. From the age of four, he witnessed domestic abuse and suffered violence throughout his childhood. At 18, he had to fend off an attack with a baseball bat at the hands of his father.

In taking a beating in the boxing ring, was he seeking comfort in the familiar?

Greaves tells me that he secretly hoped to die in the ring: “I've fought suicidal thoughts since I was a young kid. I've come very close to ending my life a few times. People can look at it and say it's a coward's way out. For me, dying in a boxing ring would have been perfect, because I wouldn't have been labelled a coward, or walking away from my family. I would have died a hero.”

He shifts in his seat, then adds: “That's quite a tough thing for me to say.”

Without boxing, life for journeymen can feel empty (c. Kia Abdullah)

Without boxing, life for journeymen can feel empty (c. Kia Abdullah)

Former journeyman Liam Griffiths, 38, also had a troubled youth: drugs, violence and spells in jail from the age of 15.

At 20, Griffiths rediscovered a childhood love of boxing and began to fight as a journeyman on the unlicensed circuit.

He speaks of this time fondly and casually recalls how he would sometimes sleep rough if it allowed him to fight. He quickly clarifies that he only did this when he missed the last train home and that it was never as bad as it sounds.

“Like in Gatwick, I’d just go up and sleep in the old terminal bit. I'd just get the first train home,” he says, adding: “I'd have four or five hundred quid in my pocket. It didn't matter to me.”

In 2011, at the age of 24, Griffiths got his professional license. Over the next 14 years, he racked up 101 fights with 6 wins, 94 losses and 1 draw. At one point in 2014, he fought five times in five weeks.

Liam Griffiths took five fights in five weeks up and down the country

Griffiths has a litany of injuries, but credits the sport for saving him: “I love boxing. Without boxing, I'd be, who knows, probably a smackhead.”

Though people look at his losing record and say “horribly negative things”, Griffiths is proud of his career as a journeyman. It takes skill, determination, grit, intelligence and cunning and, he says, most people simply couldn’t do what he did.

Griffiths has collected several injuries over his career as a journeyman. (Image: Peter Byrne/Alamy)

Griffiths has broken his nose four times. On one occasion, he broke it within weeks of it healing. “I was handsome for six weeks,” he quipped in our interview.

He over-extended his left elbow during a sparring session. In his 7th professional fight, he had to switch hands for his power punch. To this day, it's painful if he over-extends.

Griffiths has sustained damage to his eardrums.

Griffiths has a labral hip tear on his right hip. He no longer runs while training.

For journeymen, the benefits are clearly mixed. The fans, meanwhile, don’t seem to mind the system. Several told me that they prefer it to the death of small hall boxing.

Samar Habib, a multimedia designer and avid boxing fan, credits journeymen for building the careers of boxing's biggest stars.

He says: “Someone like Anthony Joshua was groomed for success from the time of his Olympic triumph. His continued professional success has brought in multiple millions of dollars into the sport, and the sport benefits hugely from his success – which, in no small part, was made possible by his early professional opponents giving him ring time.”

Pundits describe elite boxers as modern-day gladiators. Fighters like Anthony Joshua are likened to these ancient warriors. If, however, we look at who the gladiators were – men from the lowest echelons of society, doomed to lose to please a crowd – it is clear that journeymen with their broken bones and homes are the sport's real warriors.