Britain's oldest synagogue cast into shadow?

Deep in the City of London a bitter fight is being waged over a patch of sky

On one side, a developer with plans to build a 45-storey office block

On the other, the rabbi of Britain’s oldest synagogue

Rabbi Shalom Morris is defiant. It’s now the fifth year since he went into battle with developers aspiring to build a skyscraper a stone’s throw from his synagogue - but he’s not about to give up the fight.

He says the proposed 45-storey tower would cast the historic Bevis Marks temple into shadow and block the view of the moon from its courtyard.

Most people would take a dim view to a loss of light, but Rabbi Morris claims it would also strike a devastating blow to the religious life of his congregation.

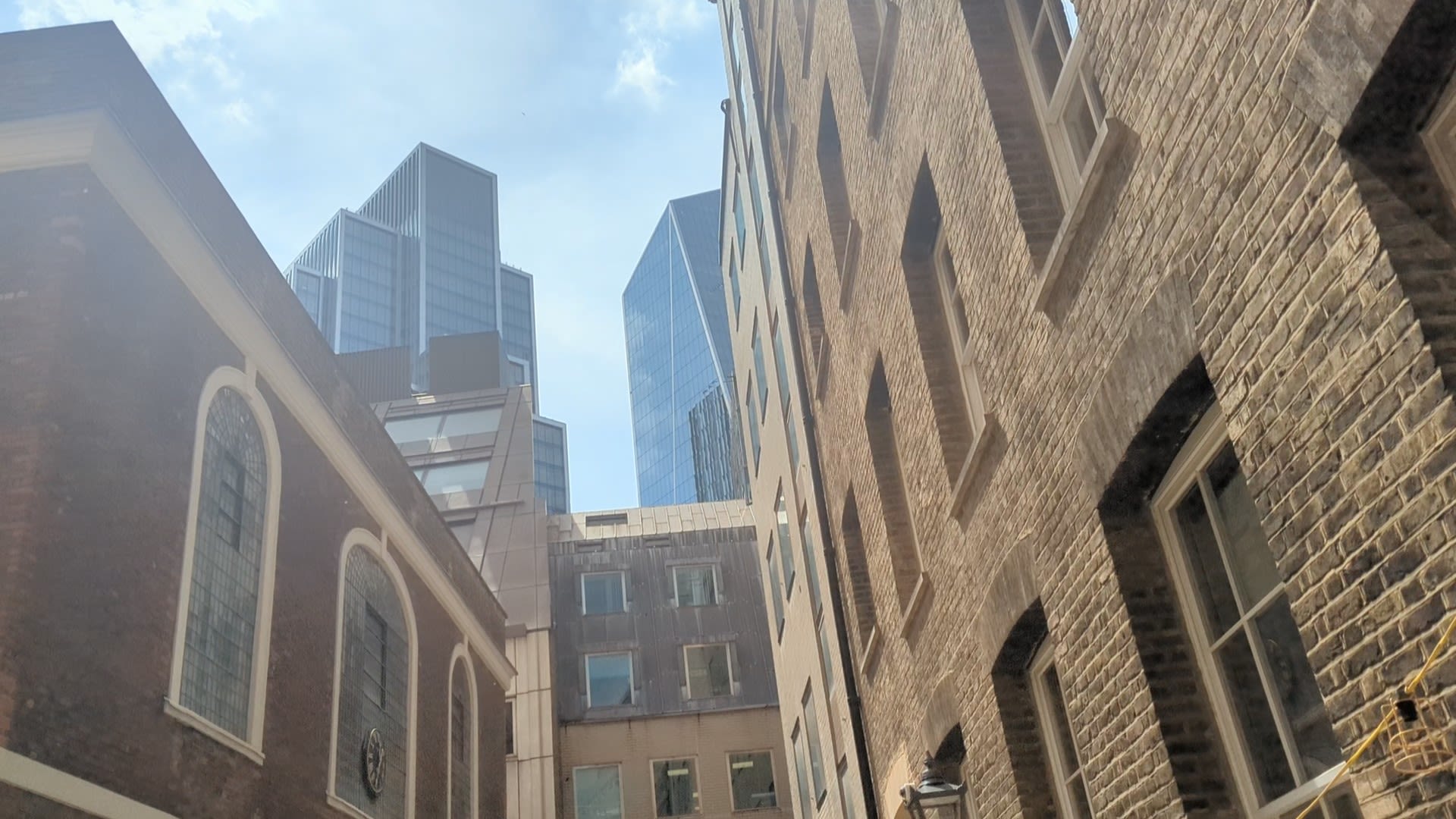

In 2019, the developers, Welput, applied to the City of London Corporation for permission to erect a 48-storey tower in neighbouring Bury Street, 25 metres from the synagogue.

The application attracted over 1,700 objections. The Corporation deferred its decision, and in 2021 Welput submitted a revised proposal, which was rejected later that year. They appealed and were rejected again. But in January this year they tried once more, after reducing the height to 45-storeys.

Rabbi Morris claims this would make little difference. He says the synagogue would still be starved of light during the day, while at night the view of the moon would be blocked.

Bevis Marks is the oldest synagogue in the UK and has been in continuous use for longer than any synagogue in Europe.

It was founded by Spanish and Portuguese Jews who had fled from persecution in the Iberian peninsula. For the Jewish community, its status is comparable with St Paul's Cathedral.

Built in 1701, before the advent of electricity, by day the synagogue relies on its stately clear glass mullioned windows to let in the light.

By night, the space is lit by over a hundred candles flickering from ornate brass chandeliers that hang from the ceiling.

There are few electric lights and Rabbi Morris believes that installing them would damage the building’s character.

“This is a Grade I listed building. For a building of this age the objective is to maintain it in its original use as much as possible.

“To put in massive fluorescent lights would obviously detract from the historic quality of this building. If preserving the heritage of England is of value, then it’s about preserving a building to be used as it has been for centuries. It would be substantial harm if we had to erode a building of this significance.”

Video credit: Rabbi Shalom Morris

Video credit: Rabbi Shalom Morris

The passage of the new moon, from the courtyard of Bevis Marks. The proposed tower would block the view as it passes over to the right side of the synagogue.

The moon is of great importance in Judaism, as it is used to define time. Jews follow the lunar calendar, rather than the solar one.

The beginning of each lunar month in the Jewish calendar is called Rosh Chodesh in Hebrew, which translates as the “head of the month.” It is considered a minor festival, with its own special prayers - the kiddush lebana - and rituals.

At Bevis Marks, Rabbi Morris says, they have their own particular tradition to mark the advent of the new moon:

“Every month on the appearance of the new moon in the sky we come out here, see the moon in the sky and say a prayer for renewal – just as the moon is renewing so our community should renew as well.

“If a building was built there it would block that view and we’d no longer be able to recite that prayer on a monthly basis.”

Daylight is crucial for for the synagogue, for both practical and religious reasons. Jewish prayer times, for example, are determined by the daily course of the sun.

“According to Jewish law,” Rabbi Debbie Young-Somers from the Edgware and Hendon Reform Synagogue explains, “there's a certain amount of natural light that needs to be able to get in through the windows.”

“We are encouraged to ensure the light can get in. So you'll quite often have ceiling windows to allow as much light to enter as possible.”

“When buildings keep going up, that is going to make it increasingly difficult. There's already a lot of skyscrapers in the area.”

Photo by Toa Heftiba on Unsplash

Photo by Toa Heftiba on Unsplash

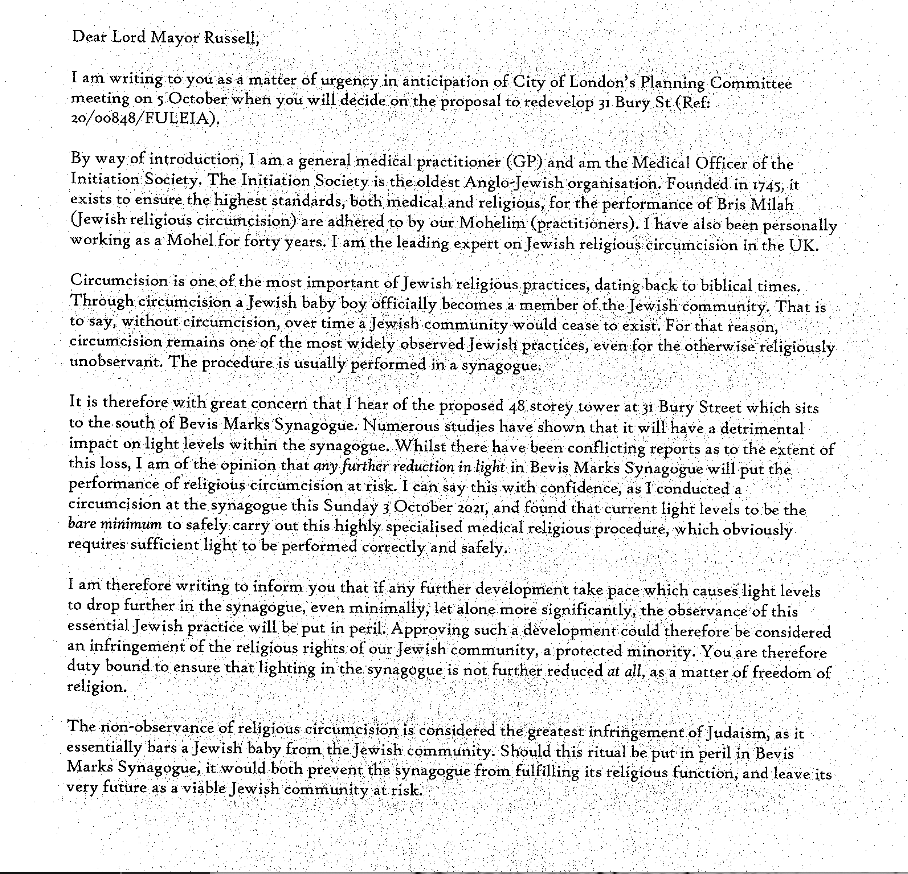

One practice is particularly at risk.

Lowered light levels in the synagogue would mean it may no longer be safe to carry out circumcisions.

In a letter (seen on the left) to the Lord Mayor of London in 2021, Dr J Spitzer, a prominent mohel (the Hebrew name given to those who conduct the procedure), stated that: “if any further development takes place which causes light levels to drop further in the synagogue, even minimally, let alone more significantly, the observance of this essential Jewish practice will be put in peril.”

Bevis Marks Synagogue contains two historic circumcision chairs from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, testifying to the long history of circumcision there.

Ending the practice of circumcision at Bevis Marks, campaigners say, would mark a significant rupture in three hundred years of tradition, harming its significance as a place of worship and communal life.

Image credit: Rev Josh Harris

Image credit: Rev Josh Harris

City of London clergy at the Corporation's Guildhall offices after presenting a letter in support of Rabbi Shalom's campaign.

Neighbouring Anglican clergy have thrown their weight behind the campaign. In May, local vicars marched on the City of London Corporation with a letter backing Rabbi Morris.

In it, they stated they were “deeply worried by a regressive restriction of freedom of religious practice.”

They pointed out their concern that the only community directly affected by the planning application was “the only synagogue – indeed, the only dedicated non-Christian house of worship – within the City.”

“Particularly at this time when our Jewish brothers and sisters feel under considerable threat, it’s so important to make clear they are welcome and not put their survival in jeopardy.”

Welput were unavailable for comment. But in an earlier statement to the Architects’ Journal, a spokesman said: “Our Bury Street project seeks to maximise heritage, environmental and public benefits by considering the future use of the entire site.

“We have a sincere respect for the historic and cultural importance of the area around this site, including Bevis Marks Synagogue.”

Image credit: Corporation of London

Construction is booming in the City. Eleven skyscrapers are due to be built in London’s financial district by 2030, as shown in the image opposite.

More than five million square feet of office space is currently being built, with another five million square feet to come.

This is part of the City of London Corporation’s vision for the district’s economic growth, and its aim to entice businesses back to area from its rival, Canary Wharf, a few miles downriver to the east.

The City is the oldest part of London and has always been the capital’s business heart. Over the ages, the Jewish community has made a significant contribution to its status as a financial hub.

Now, as it strives to maintain its place in the financial world, is the City in danger of extinguishing its Jewish heritage?