Are children reading less?

An overview of children's literature in the seventy five years since Enid Blyton's The Secret Seven was published

Seventy-five years ago, Peter, Janet, Pam, Barbara, Jack, Colin and George burst into children’s lives as Enid Blyton’s “Secret Seven”. The Secret Seven was a society of young detectives who solved mysteries in their neighbourhood, complete with badges, passwords, a headquarters and a cocker spaniel named Scamper for company. The children took their roles very seriously, and it was often through their amateur shadowing practices that they ended up solving real crimes: locating stolen dogs, for example, or uncovering a bonfire night plot. The Secret Seven is characteristic of the Blyton universe, school children who sneak out after dark, overhear things that they shouldn’t and enjoy picnics with lashings of ginger beer in their free time.

For decades, it seemed like almost every child in the country was reading Blyton’s stories, about young detectives, the alluring world of boarding schools or magic. Malory Towers remains so popular that it was turned into a CBBC series, and it was recently announced that The Magic Faraway Tree will get the same treatment. The Secret Seven hasn’t yet been realized on the small screen, but in 2018 the children’s author Pamela Butchart published the first of her continuations of the beloved children’s series, The Secret Seven: The mystery of the skull, commissioned by Hodder Children’s Books. In 2017, according to Butchart, an Enid Blyton book was sold every minute. Evidently there remains an appetite for Blyton’s ordinary worlds and her memorable characters. That being said, Blyton’s oeuvre still contains racist, xenophobic and sexist comments and some aspects are informed by the legacy of colonialism. Today, young readers can find themselves much better represented in the children’s publishing market, which offers a far broader range of stories, breaking the mould of Blyton’s similar characters and representing many more lived experiences.

Filmed and edited by Lily Herd | Locations: House of Books, Muswell Hill Broadway; Children’s Bookshop, Fortis Green Road | Music: Happy Days by FSM Team via https://free-stock-music.com/fsm-team-happy-days.html

Filmed and edited by Lily Herd | Locations: House of Books, Muswell Hill Broadway; Children’s Bookshop, Fortis Green Road | Music: Happy Days by FSM Team via https://free-stock-music.com/fsm-team-happy-days.html

However, this anniversary coincides with fewer children than ever reading for pleasure, according to the National Literacy Trust (NLT). In the annual Children and Young People’s Reading survey, the NLT found that fewer children enjoy reading for pleasure than at any other point since they started surveying young readers in 2005. This year, of the 70,000 young readers aged 8-18 that were asked, only two in five (43.4%) answered that they enjoyed reading “very much or quite a lot”. Martin Galway, Head of Schools Programmes at the National Literacy Trust, explained that this bracket describes children who read of their “own volition”, and, regardless of whether they were the one to pick up the book, have “carried on with a desire to know either more about something, or because they’re … enjoying it”.

Children’s reading does not just lead to a stronger grasp of language and higher academic performances, although these are certainly long-term impacts of an early love of reading. Galway explained that children who read of their own volition have a “greater facility for resolving problems” and “stronger measures of empathy”, while there is a traceable chain for those that struggle to love reading, extending to “reduced chances of employment … heightened rates of social enjoyment [and] potentially … future crime”. While these are the most severe effects of a lack of enjoyment of reading, he also stressed that children who enjoy it have a greater sense of “personal satisfaction”.

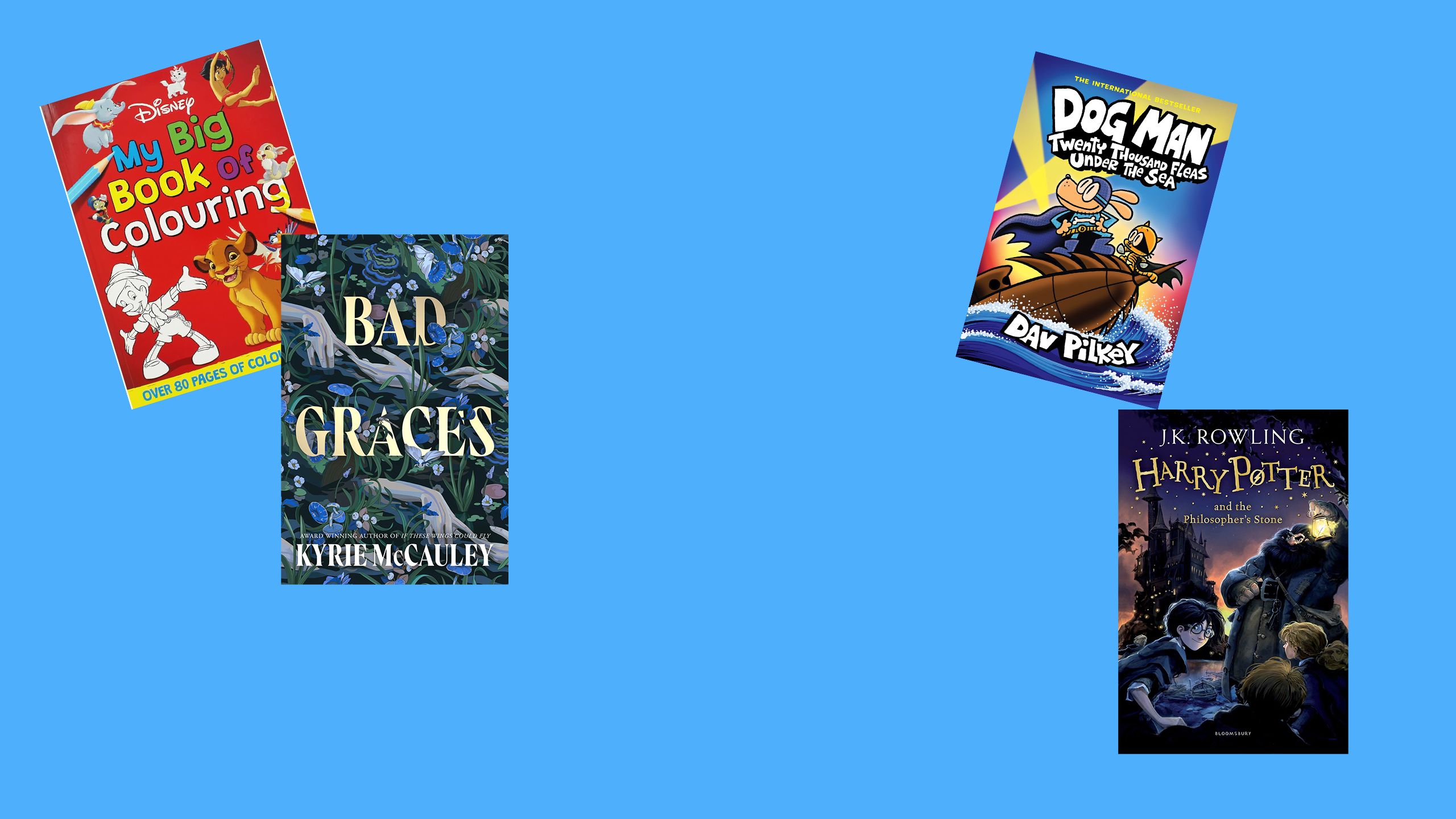

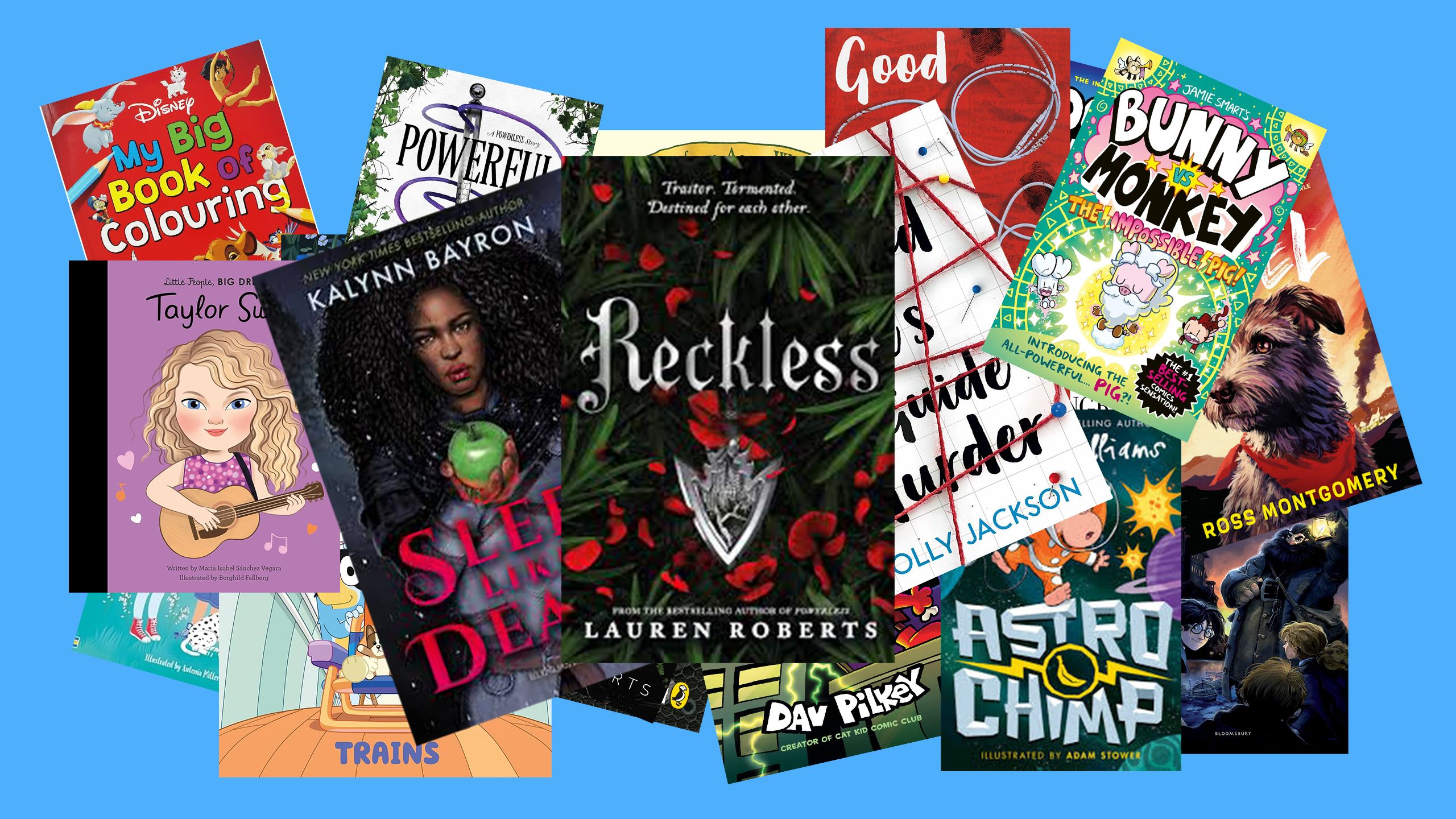

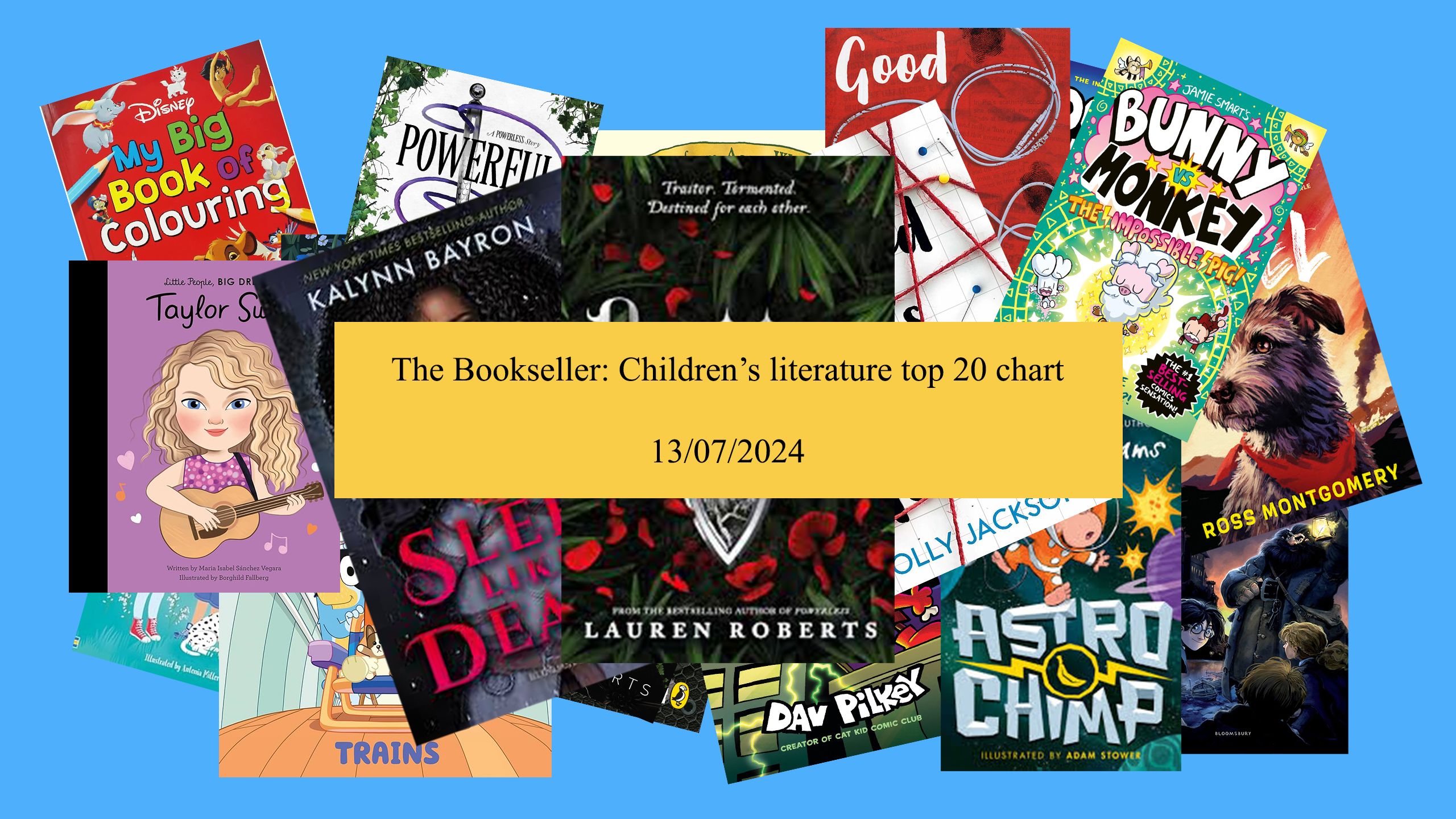

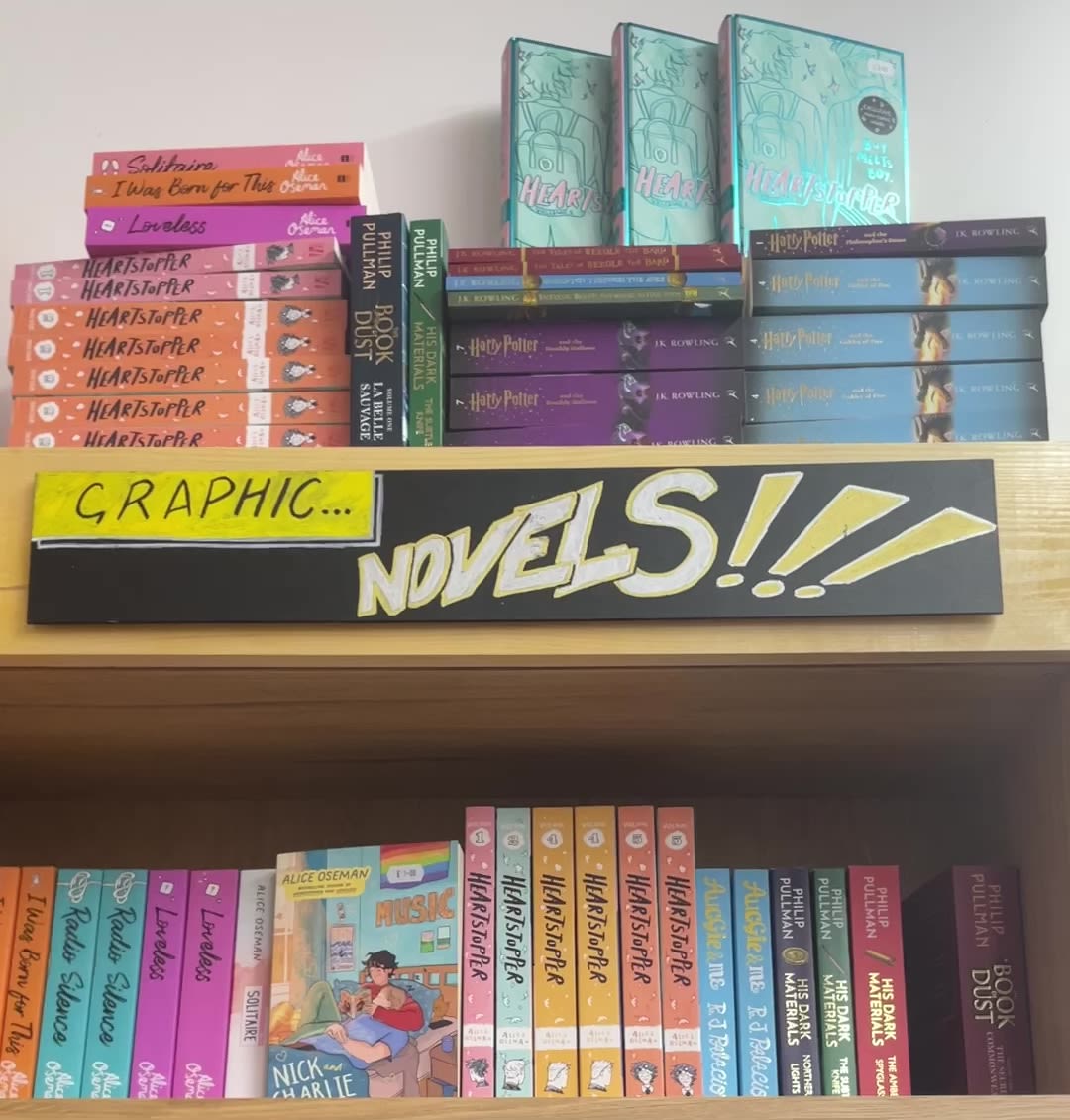

It is important in both the long- and short-term, then, to encourage a love of reading in young people. Despite the concerning statistics, the children’s literature market is full of creative narratives, diverse characters and fantasy worlds. Recent publications for young readers include Wolf Road, about a Neanderthal boy and a prehistoric girl, Transcendent, in which a set of Ugandan twins undergo competitive training to join a dangerous space mission, and Nine Night Mystery, set during the traditional Caribbean funerary celebrations. Graphic novels are also very popular. Galway said: “I think we should lean into that – if librarians are saying we're finding it hard to keep graphic novels and comics on the shelves, that's something we need to capitalise on.” There are also several celebrities in children’s bestseller charts: Chris Colfer, Jamie Oliver, Greg James and Alexander Armstrong, to name a few. In addition, Galway said: “There’s no denying that certain books reappear time and time again in most reading lists – your Harry Potters, Roald Dahl, David Walliams [and] The Diary of a Wimpy Kid series.” Newcomers that have drawn the attention of the Trust include Jamie Smart’s comics, Dav Pilker’s Dog Man series, Jennifer Killick’s books – which are “quite scary, slightly edgy, and children really gobble those up” – and Christopher Edge’s sci-fi. Galway also observed that “the quality of children’s nonfiction publishing has gone through the roof”.

Children’s literature is partly championed in the UK by the children’s laureate, recently announced for 2024-2026 as Frank Cottrell-Boyce. This is a role awarded on merit, and the laureate’s task is to improve opportunities for reading for all children in the UK – as the NLT survey shows, this is a desperate priority for 2024. Each laureate takes on a specific area of children’s literacy, including poetry, reading out loud and promoting libraries. According to the BBC, Cottrell-Boyce will specifically focus on “starting a much needed national conversation about the role books and reading can play in transforming children’s lives”. Previous laureates include many of the children’s literature titans: Michael Morpurgo, Michael Rosen, Jacqueline Wilson, Julia Donaldson, Malorie Blackman.

I spoke to Lauren Child, children’s laureate 2017-2019, about the responsibilities of the role. She said: “I really wanted to get us all to think about childhood and the purpose of it – and the idea that childhood stays within us because it becomes part of the bones of us and who we are. All of our early years experiences are very powerful.” She used the position to nurture children’s creativity and to encourage “dream time and allowing ourselves space to think” in order to practice writing. Regarding the decrease in children’s enjoyment of reading, Child said, sadly, that she thought it was somewhat “inevitable” and she connected the NLT’s findings to a broader reliance on screens (not just among young people). She said “this lack of focus that so many of us are experiencing now – that really worries me”. In terms of reading, she warned that “we’re all losing something that’s incredibly nourishing”.

Child’s latest novel, Smile, deals with anxieties about climate change. In June 2024, the charity Action for Conservation found that almost two thirds of children between 11 and 16 suffer with eco-anxiety. In Smile, Child’s beloved character Clarice Bean is fighting to save the trees on her street from being uprooted, which would make the pavement seem tidier and less bumpy. The entire novel takes place within Clarice’s community, but the at-risk trees stand in for more existential anxieties faced by children who cannot feel optimistic for the future of their planet. Smile is about finding solutions, no matter how small, even when everything feels impossible. Child considers it her role as a children’s writer to strive for a balance about telling the truth to children, because they have “natural antennae” to pick up on what’s really going on, but also not to leave space for feelings of despair. When I asked what it means to her to write for children rather than adults, she described it as “having a responsibility to give hope”.

Child told me that the story was born out of her own anxieties about the state of the climate. She explained, “The only thing I could write was Smile because I was feeling kind of desperate and I transferred that worry to Clarice because I couldn’t solve it … It was really interesting looking at something through a character’s eyes and thinking ‘what would she make of this?’” Twenty-five years on from the first Clarice Bean story, Smile’s themes tie in with the developments in children’s characters to have broad and realistic ranges of experience: children’s literature seems to reflect children’s lives more than ever.

Read my review of Smile in this week's TLS:

“I really wanted to get us all to think about childhood and the purpose of it – and the idea that childhood stays within us because it becomes part of the bones of us and who we are.”

Lauren Child | © David Levenson/Getty Images

Lauren Child | © David Levenson/Getty Images

This quiz comes from a list of the 100 greatest children's books of all time, compiled by BBC Culture in 2023